Fort McMurray, Alberta

The Elusive Self

As a young man, I was enamoured with Buddhist and Hindu doctrines about the nature of the self. Buddhism teaches that it is a purely ephemeral invention. Sensations trick the mind into bifurcating the world into the categories of self and other. The Buddha, however, teaches that this distinction is responsible for the suffering of man and his entrapment in the cycles of Samsara. Desire spawns suffering, and it is the self which desires; when the self ceases to be, so does desire. To achieve Nirvana, the self must be abolished entirely.

The Hindu philosophy of Yoga, similarly, aims at attaining a state of Kaivalya (detachment) through the practitioner discriminating between Prakriti (cognitive apparatus) and Purusha (pure observer), the latter being the true self, while the former is entirely incidental. We are all only Purusha, pure essence, disinterestedly observing the world around us, whereas characteristics—physical or psychical—which we attribute to the self are all worldly.

That ephemerality of the self is an idea by which I was long enticed. It reached me when I was at a point of skepticism with regards to the idea of an immutable and essential self, after having studied the contemporary metaphysical quandaries concerning questions of personhood and personal identity. I found all the theories explaining what a person is and how that person persists over time to be unsatisfactory.

Theories of personal identity attempt to define personhood in terms of corporeal existence, mental states, continuity of memory, continuity of consciousness, continued life narrative, one’s particular genetic structure, or even as series of relations. All of these explanations, in my judgement, fail at one point or another. In practice, it seems as if any one of these is invoked ad hoc to justify rough intuitions about what a person is. But each alone is insufficient. It is far too easy in this position to throw one’s hands in the air and declare the self to be ephemeral, just as Parfit did.

Perhaps the self is nothing at all; perhaps it is an illusion. Maybe man is a blank slate upon which the world impresses itself. Perhaps man is a chameleon, adapting to any circumstance, no matter how harsh, and becoming what the world demands of him. Or, perhaps man is what he wills himself to be, creating himself anew at every moment. Perhaps it is this pure will alone which underlay man—nothing of essentiality. One with a strong enough will may make himself anything he wishes to be. Perhaps this skepticism towards the self was partly a Nietzschean hangover.

When I left my home to work in the Canadian frontier, what I expected to find was that I would change drastically under such different circumstances, that I could become a different person, and either forge a new identity for myself, or be radically reformed by the new and harsh environment. I thought a new age demanded a new man. I expected to be broken and reformed under toil; I expected to reveal a blank slate.

What I found was the exact opposite.

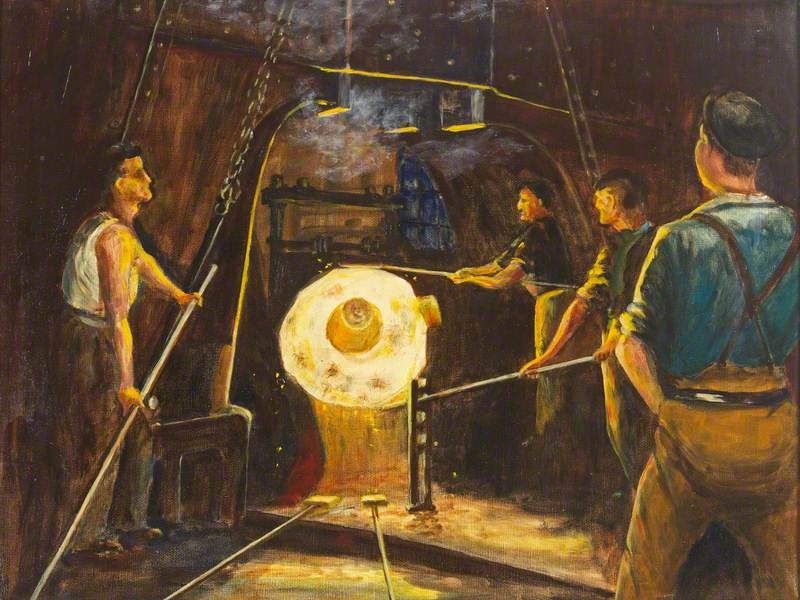

The Lesson of the Frontier

In fact, what I discovered while busting apart wellheads in the frozen northlands, with my kneecaps frostbitten from kneeling in the snow and my hands blistered from reefing on wrenches, was that I am something.

It is repetitive and hostile toil in which I caught glimpses of my essentiality, not as absence but presence. What I observed in myself was not mere flux—on the contrary, I saw the contours of my Being. Traits I had long observed in myself reappeared in diverse forms. Latent characteristics emerged—some of which I had long known, some which were previously vague intuitions, and some which were entirely new and unexpected. But most of all, it was continuity, not difference. When ripped from what was known and placed in a strange and foreign environment, I understood myself best as a man with an irreducible essence, not as malleable clay.

Heidegger wrote that it is in “everydayness” that the Being of man is disclosed. I contend that it is only when he is ripped from his life in the sterile modern world and put to work in a foreign land that the triviality and accident are cast off to reveal pure Being.

What struck me was how unmalleable a man actually is. In society, pretension and performance are not only allowed, but they are demanded—leading readily to a crisis of identity and the loss of one’s self. It hardly bears saying that Western man is facing a crisis of identity. In the north, however, there is simply no room for such pretense. When man is subjected to a difficult physical task, what is present deep within him shines forth. Whether he is strong or weak, spirited or slothful, joyous or miserable, virtuous or vicious, is revealed through work. When a man labours in the cold all day, there is no performance. The cold eats away at the fat, the glitter, the inessentiality, and presents him as he truly is.

In my years of work on the frontier, I have seen this firsthand. I have seen the kindest men pour forth sublime rage, and I have seen the most stolid of men weeping bitter tears. Standards of etiquette picked up in society quickly fall away. Diction becomes coarse and candid. Men say what they mean; more often, they holler and scream. I have seen many men whose inner vitality was kindled to life, and many more whose guise of strength crumbled under pressure. I have seen many men who simply could not take it.

The revealing of one’s essence occurs in work through a dialectic mediated by the Task—the assignment as given by an other. The Task is essentially the forced confrontation with otherness in work, demanding the self to be projected through labour, to bounce back against this other, and finally be returned, when a man finally knows himself and feels at home in his labour. Man enters into a dialectic between him and this Task, in which the drama of self-discovery plays out through three distinct phases.

I. The Question of Motivation

Man undertakes physical labour as imposed on him through the Task. When the body is active, the mind is put into the position of an observer. Because the mind and body are interconnected, the mind is privy to each and every signal the body sends, and is in a position to interpret them.

When the Task is solitary, the mind is able to finely attune itself to the activity of the body, to focus intently and savour every impulse. Without distraction, the mind is able to escape into pure inwardness. This is a necessary moment in the dialectic. Every bead of sweat, every pain and ache, every cut and bruise, is fed directly to the mind as pure data. It is in this state that the mind can assemble its materials.

Under these conditions, the mind is hardly passive. Rather, it is spurred to activity. When the Task is difficult but simple, the mind’s role becomes primarily motivational—how to impel the body to continue in its labour—or how to achieve a mental state that is conducive to performing the Task. The question of motivation arises with a moment of doubt—a negative moment such as is encountered by all men who undertake a great labour.

Motivation does not arise naturally, and so it must be provided. The Task is otherness, after all—it is assigned. Any endeavour which arises intrinsically will not suffice. Where one’s desire leads them to work, motivation is not questioned. Doubt arises with this otherness, as there is the possibility that the self is not strong enough to surmount this other.

In this negative phase, the mind faces a number of questions: what are the limits of the body? how can it be motivated? what emotions are present? what is to be done about them? what is one doing the Task for? is it worth it? is it possible? These questions demand answers. An unsatisfactory answer will not motivate the body to continue in its toil.

This necessitates that the mind probe the depths of its inwardness. For, it is only through a knowledge of oneself—the body, mind, and interaction between the two—that such answers can be provided.

The mind must employ its materials.

The mind must first isolate and interrogate desire. Desire is problematized in the Task best of all because here the mind must summon desire itself. It is desire which leads one to set a goal. There are a myriad of possible desires: fear of punishment, love of money, a desire for power, status, or glory. The mind must uncover which ones are potent enough to impel the body to action.

The interrogation of desire naturally leads to an interrogation of the will. For, desire is the faculty which directs one to a goal, whereas the will provides the wherewithal to achieve it. Through working on the Task, one comes to gauge the strength or weakness of their will. The will and the desire are the two components of motivation. When the desire can be understood and channeled, and the strength of will assessed, then the mind can provide adequate motivation.

The mind must be honest in its assessment, and it must gather its materials inductively. Where the mind is deluded, it will fail to adequately provide motivation. The obstinance of the mind may provide a roadblock, where the dialectic stops dead in its tracks.

Through the question of motivation, the line between body and mind begins to blur. One’s bodily strength is supplanted through mental fortitude—through motivation—just as motivation is cultivated through the continued activity of the body. These two mutually reinforce one another so seamlessly, that the mind begins to understand its relationship to the body.

Victor Frankl writes,

Those who know how close the connection is between the state of mind of a man—his courage and hope, or lack of them—and the state of immunity of his body will understand that the sudden loss of hope and courage can have a deadly effect.1

Though Frankl refers to his experience in a concentration camp, he reveals something universal—that mental fortitude and physical fortitude are hardly separable. The mind, which first assumed the role of observer, begins to understand itself as part of the body, as essentially connected to the body.

Through the question of motivation, man begins to understand how not only his physical, but his psychical traits also are revealed through work. Work is not merely the activity of the body. It is also the activity of the mind as mediated through the body. Man comes to knowledge of both.

After he has explored the question of motivation, man may more fully engage in the Task, and draw his attention outside himself to the thing which he is making—more specifically, the product of the Task. After he understands motivation, he moves to interrogate the product.

II. The Problem of the Product

In society, where man is demanded to perform, he does not externalize himself, but rather re-presents what he sees around him. What shines forth is only ever an adulterated image of the self, if even that.

But on the fringes of the civilized world, in working on the Task, man’s authentic self become externalized in the object of his work. What he accomplishes is an image of himself. He projects himself out into the world, and this projection crystallizes into the product.

For Marx, it is when a man does not enjoy the product of his labour that he is alienated from that labour. Marx writes, “The product of labor is labor which has been embodied in an object, which has become material: it is the objectification of labor.” However, in a capitalist mode of production, the product of labour is denied to man, instead being sold elsewhere. Marx Continues, “Under these economic conditions this realization of labor appears as loss of realization for the workers; objectification as loss of the object and bondage to it; appropriation as estrangement, as alienation.”2 It is, therefore, only in a state where man enjoys the fruits of his labour when he is at home in his work.

In modern work, it is seldom the case that a man enjoys his product. Indeed, often the product is not a tangible thing that can be enjoyed, in which case it is denied to man all the same. A man on a drilling rig does not enjoy the fruit of his labour. Nor does a welder or a pipeliner. The product is taken from him, in which case man can feel a deep discomfort—he is not at home in his work

Under capitalism, as Marx writes, this alienation from one’s labour is a most potent and tangible affliction. This result of this alienation is not only a profound dissatisfaction with work, but an awareness of the loss of one’s authentic self with the loss of the object of labour. He writes,

First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home. His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor. It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labor is shunned like the plague. External labor, labor in which man alienates himself, is a labor of self-sacrifice, of mortification. Lastly, the external character of labor for the worker appears in the fact that it is not his own, but someone else’s, that it does not belong to him, that in it he belongs, not to himself, but to another. Just as in religion the spontaneous activity of the human imagination, of the human brain and the human heart, operates on the individual independently of him – that is, operates as an alien, divine or diabolical activity – so is the worker’s activity not his spontaneous activity. It belongs to another; it is the loss of his self.3

Such passages belie a Rousseauvian pastoralism—where man is truly free in a state of nature, able to obtain ownership over things merely by infusing them with his labour, while oppression only arises with civil society and industrialism. However, Marx’s trenchant materialism makes it difficult to explain what man is alienated from if his material self is not literally in the product of his labour.

Most clearly, Marx writes “As a result, therefore, man (the worker) only feels himself freely active in his animal functions – eating, drinking, procreating, or at most in his dwelling and in dressing-up, etc.; and in his human functions he no longer feels himself to be anything but an animal.”4 However, Marx does not answer what these “human functions” are. Does a beaver not work? And would it not feel fulfilled having enjoyed the dam it has constructed? Marx is clearly aware that there is some faculty beyond mere matter which undergoes a transformation during labour—and that this faculty is particularly human.

Not only Marx, but his compatriot Friedrich Engels, observes the alienating effects of labour. Engels, less the theorist and more the observer, in his account of the English working class, describes the squalid state of workers.

[A] source of demoralisation among the workers is their being condemned to work. As voluntary, productive activity is the highest enjoyment known to us, so is compulsory toil the most cruel, degrading punishment. Nothing is more terrible than being constrained to do some one thing every day from morning until night against one’s will. And the more a man the worker feels himself, the more hateful must his work be to him, because he feels the constraint, the aimlessness of it for himself. Why does he work? For love of work? From a natural impulse? Not at all! He works for money, for a thing which has nothing whatsoever to do with the work itself; and he works so long, moreover, and in such unbroken monotony, that this alone must make his work a torture in the first weeks if he has the least human feeling left. The division of labour has multiplied the brutalising influences of forced work. In most branches the worker’s activity is reduced to some paltry, purely mechanical manipulation, repeated minute after minute, unchanged year after year. How much human feeling, what abilities can a man retain in his thirtieth year, who has made needle points or filed toothed wheels twelve hours every day from his early childhood, living all the time under the conditions forced upon the English proletarian? It is still the same thing since the introduction of steam. The worker’s activity is made easy, muscular effort is saved, but the work itself becomes unmeaning and monotonous to the last degree. It offers no field for mental activity, and claims just enough of his attention to keep him from thinking of anything else. And a sentence to such work, to work which takes his whole time for itself, leaving him scarcely time to eat and sleep, none for physical exercise in the open air, or the enjoyment of Nature, much less for mental activity, how can such a sentence help degrading a human being to the level of a brute?5

It can seem convincing in theory to posit alienation as the loss of the self through the loss of the product. Indeed, there is certainly a discomfort when a man thinks deeply about his work—that he continually produces something he will never enjoy. This can lead man into a state of alienation through his work—a loss of self. However, this only turns out to be another temporary stopping point in the dialectic. Once more attention is given to Marx and Engels’ arguments about alienation, a way out is revealed.

Despite their materialist bent, these thinkers admit some higher element in man which is foregone when work reduces him to a bestial state. However, if man is only matter, then nothing differentiates him from beast and, moreover, materialism provides no grounds to suggest that this human component is non-material or superior to a bestial existence. It is also difficult to explain how the self is in the product of labour, aside from in a purely symbolic sense.

That there is something non-material and “human” embodied in the product of labour implies consciousness. For, first, consciousness is the unique thought patterns that are able to work through the body to make a thing that reflects it, and, secondly, the means of recognizing traces of the self in the product of labour. Alienation requires this recognition, which hinges upon consciousness (a beaver can hardly be said to be alienated from its labour if deprived of its dam, after all), and a unique consciousness proper to a man is necessary for the product of his labour to reflect him particularly, rather than any other man.

But consciousness is not abolished in the Task. Rather, consciousness is a necessary condition for the phase of alienation to occur at all. It is this which separates man from beast within the framework of Marx and Engels, as it is this which allows men, and not beasts, to experience alienation. Marx and Engels want to have their cake and eat it too—to posit that man’s human element is denied in labour, but also that this human element is necessary to recognize their alienation. Consciousness remains within man, no matter how much it is projected into the world. Where, then, is alienation?

Interestingly, these accounts came from individuals who had never performed manual labour in their lives.

When the product is in front of him, man becomes enthused with his creation. He may fall in love with it and dwell upon it. On the other hand, when this product is denied to him, it is a shock, certainly, but it is this shock alone which allows the dialectic to proceed. Through the problem of the product, man’s awareness is redirected away from the other and back towards the self. If it is through work that recognition of this “human element” arises, perhaps it is not in a negative sense, as with alienation, but a positive sense.

This brings into focus the way in which the Task is accomplished, as it is this way to which man can lay claim. Marx rightly observes that the product of labour is the focal point for many men. But where a man is denied this product, where he is no longer invested in it, where he meets opposition in the Task, he brings his attention back from the product, and towards the self in making the product.

III. The Interrogation of the Way

Without the product, the way in which man does the work becomes the most indicative of his nature. As Hegel writes,

“. . . work forms and shapes the thing. The negative relation to the object becomes its form and something permanent, because it is precisely for the worker that the object has independence. This negative middle term or the formative activity is at the same time the individuality or pure being-for-self of consciousness which now, in the work outside of it, acquires an element of permanence. It is in this way, therefore, that consciousness, qua worker, comes to see in the independent being [of the object] its own independence.”6

While some might see work as servile, for Hegel, this seemingly servile state is one in which man realizes his own independence and self-sufficiency. Work thus constitutes a kind of self-reflection, but one which takes place outside the body, in which one’s self is projected into the world, infused into an object, and reflected back into oneself.

This dynamic is presciently captured in Hegel’s lord and bondsman dialectic, wherein the lord rules over bondsman and assigns him work. However, in an eternal irony, it is through this work that the bondsman becomes aware of his self-reliance and freedom, as well as the power he wields through this self-sufficiency, and on this basis is able to oppose the lord. It is through the oppositional relation between lord and bondsman, and through the bondsman’s work, that the bondsman is made truly self-aware. This can only happen through a skirmish with otherness, just as with the Task.

This need not be abstract. It is he who physically works who understands how to do essential things for survival, while the one for whom he works does not.

However, Hegel is not entirely correct. For, what the bondsman discovers in his Task is not his freedom—at least not entirely. Rather, what he finds is a brick wall: his unchanging underlying essence.

The self shines forth in a man’s way. When he is at work, he makes the Task his own not by appropriating the product, but by mastering his technique. This is partly the skill with which he performs the task, but the way is more fundamental—it is the entirety of how he goes about undertaking the Task.

A man’s way is infused with character and personality. Adversity causes his true colours to show; when he is at home in the Task, he makes his own mark upon it. Being denied the product is only a temporary alienation, as in the way, he sees himself most clearly.

Through the jokes he makes, through his method and technique, through the stickers on his hard hat or the ornaments on his rig, through his unique demeanour, special tricks, eccentricities and idiosyncrasies, man’s innate dispositions are revealed.

Moreover, a man does not create his way, but finds it. This is crucial, as it cements the connection between self and way. His way is an authentic indication of him. A way, furthermore, is timeless. It is the continuity of the way which invokes the dead, by which we remember people. It is deviance from a man’s way that we detect something amiss. But we would do well to go further, and assert that the way is not itself timeless, but indicative of something timeless.

Man does not create a way, but his way forms him. He is confined to the way, being a more fundamental expression than even the product. It is more fundamental because it is more immediate. At every moment in his labour, a man’s essence shines forth in his way. He must be acutely aware to notice this and recognize its significance, however.

The way is a middle ground between self and other (as in the Task). It consists of pure activity, not embodied activity. The way, upon investigation, is something real and determinate, and this understanding similarly allows the mind to posit something real and determinate mediating body and soul. Rather than mind underlying body, as was supposed through the question of motivation, something more fundamental underlay both mind and body, facilitating the interaction between the two.

Work breaks down accident and leaves essence in plain view. The Task, which directs a man away from his natural tendencies and demands that he change (via the imposition of otherness), brings all that cannot change into focus. It is then understood that man possesses certain characteristics, motivations, desires, habits, and thought patters which persist across time and space. Discovering these through self-reflection alone is perhaps impossible, for it is not immediately apparent what is innate and what is imported. But through work, this is revealed.

These traits are both bodily and mental, existing neither in consciousness nor the flesh alone, but in the interaction between the two. It is only when the mind understands itself as deeply interconnected with the body that such insights arise. However, mind and body alone are neither sufficient to explain this interaction. When traits can remain hidden for so long before coming to light suddenly this suggests that there is some liminal space they reside between mind and body.

As such, to explain where these traits are located, we must posit that something more fundamental than either body or mind exists. This idea, a theory of personal identity which has long since fallen out of fashion, is that there is an immaterial and immortal soul which persists across time and space and which facilitates the hitherto inexplicable link between mind and body. I wager this is the “human function” of man to which Marx and Engels alluded but could not admit.

I mean “soul” in the Platonic sense, as the immaterial aspects of a human being which persist over time and inform our actions. However, now we know that the causal relationship also works the other way—that our circumstances, to varying degrees, shape our souls. That things such as personality, beliefs, and mental characteristics are heritable and expressed in one’s genetics can be seen not as evidence against an immaterial essence within humans, but rather, as further proof that the material and immaterial aspects of man are unified in myriad mysterious ways.

The way qua activity suggests the necessity of soul as the purely active agent behind both our mental and bodily activity. Soul’s activity is essentially mediating mind and body. The Task suggests that man’s essentiality lies in his activity, and the soul is the only theory of personal identity which venerates an active agent, rather than a static and rigid fact such as memory or body.

Helmuth Plessner (1892-1985), a German thinker who pioneered the field of philosophical anthropology, sees the relationship between mind and body to constitute the essential human condition. He doesn’t use the word “soul”, but we don’t need to quarrel over terms. For Plessner, man is characterized by his eccentric position, by both being a body and having a body. He finds both purely materialist and mentalist accounts of the human essence to be facile. Instead, what is essential about humans is the interaction between mind and body. The dual position of being integrated in a body, but also being able to stand outside oneself and observe, is what differentiates humans from animals, which are merely integrated into their bodies but unable to stand outside themselves in reflection.

Man’s eccentric position, for Plessner, is most visible in the distinctly human phenomena of laughing and crying. These two expressions are not merely emotional, nor automatic physical reactions, but are fundamentally rational. It is only through the understanding that something may be appreciated as funny or sad, after which the body reacts in place of the mind. Plessner writes, “with laughing and crying the person does indeed lose control, but he remains a person, while the body, so to speak, takes over the answer for him. With this is disclosed a possibility of cooperation between the person and his body, a possibility which usually remains hidden because it is not usually invoked.”7 In essence, laughing and crying are so important to Plessner because they are simultaneously rational and bodily responses, demonstrating a perfect but inexplicable unity between mind and body.

Exactly what is mediating these two things is left unanswered in his account, however.

What is revealed to Plessner in laughing and crying is also revealed in work. Where Marx’s account of estranged labour goes awry is his materialist assumption of man merely being a body. Hegel, contrarily, takes the position that spirit merely has a body—and without the limitations this body imposes, he was able to declare freedom to be the fundamental human essence.8 Neither is true. The dialectic of the Task reveals a complex nexus of relations, between freedom and limitation, mind and body, self and other, spirit and matter, which the human being uniquely holds together in equilibrium. The self, the soul, is precisely this nexus. Each theory of personal identity fails because they assume the self to be something static, rather than something active—and, though relational, still determinate. The soul neither blends into everything else, nor is something you can pinpoint, saying “here it is.”

The soul is the mediate link between body and mind, in which dwell the inner recesses of man’s Being.

There is little evidence that this dialectic is consciously experienced. And it does not need to be. Thought processes are seldom experienced consciously, in any case. Indeed, the self-knowledge cultivated through it may not even be explicit. And it need not be so. The self-knowledge manifests as a deep at-home-ness which can be readily observed among the men of the frontier.

Nor is it a necessary progression, as there is the possibility that a man stops halfway—the Task is too much for him. But it is experienced by all men who undertake the Task successfully and make their work their own.

Work and the Crisis of Identity

In an age where nothing is more spoken about, but less understood, than personal identity, self-knowledge becomes more important than ever. Western society is obsessed with identity—with answering questions of “Who am I?” and “What is the authentic me?”

Though they are, of course, superficial, these questions arise so persistently, with people finding increasingly obscene answers, that we must diagnose society with a malaise of identity. This phenomenon indicates a few things. Firstly, that people have the leisure to ask such questions; secondly, that there is something peculiar about our age and place which leads the topic of personal identity to be problematized; and thirdly, that people are dissatisfied with the answers which have been heretofore provided to the question of personal identity—though this is not necessarily indicative of their failure.

Social ills seldom have a single identifiable cause. However, if all that I have said is true about the importance of labour for one to know the contents of their own soul, and the current unpopularity of the very idea of the soul, then it is possible that the modern crisis of identity may be caused by the absence of physical labour in our society. One accurate prediction of Marx and Engels was that technology would make work far less physically strenuous in the future. This change cannot be entirely condemned, though we can acknowledge the problems which arise as a result.

The economies of developed Western nations are increasingly dependent on the service sector, rather than primary resource extraction or manufacturing. We have seen, over the last couple of centuries, the rise of bureaucracy, managerialism, and “bullshit jobs,” which, as David Graeber points out, are psychologically destructive.9 It seems like such pointless and effortless jobs are far more alienating than any type of factory work ever could be.

Where man does not work, he cannot fully know himself. As physical work becomes less common with technological advancement, the only chance to experience the Task as such is the frontier. There are few genuine frontiers left on this earth. These places must be actively sought out, for they are disappearing quickly. But it is these places where man may ripped from his everydayness and shown the contents of his soul.

In an age where no one is precisely sure of their own identities, men cling to features like race, nationality, sexuality, gender—all things which bestow upon them a sense of meaning, yet are ultimately incidental. These things, as purely material, do not reveal a man’s essence. Either this, or there is incredulity towards the very idea of personal identity. This explains an increased interest in Eastern conceptions of personal identity as ephemeral, as well as such views being increasingly adopted by notable Western thinkers, including Derek Parfit, Graham Priest, or James Giles.

In urban centres it is easy to assert that there is no such thing as the self. In Fort McMurray, it feels impossible.

This crisis of identity in society at large starkly contrasts the quiet confidence and simplicity of the working man. He hardly needs to scour the world over to find what he is, but is content with a beer and sports television after a long day at work. To say that the archetype of the working man is one of simplicity is hardly an insult, as simplicity belies a humble confidence born of a deep self-knowledge. Where man has cultivated such a deep self-knowledge through his work—whether it is expressible in words, or merely through his embodied understanding—he cannot but be simple.

Personal identity turns out to be quite a simple matter after all. A man is but a soul sprinkled with accident.

Frankl, Victor, Ilse Lasch trans. Man’s Search for Meaning (2008), pp. 84.

Marx, Karl, Martin Milligan trans. “Estranged Labour” in Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1932), XXII.

ibid, XXIII.

ibid.

Engels, Friedrich, David Price trans. The Condition of the Working Class in England (2005), pp. 119.

Hegel, G.W.F., A.V. Miller trans. Phenomenology of Spirit (1977), §195.

Plessner, Helmuth, Marjorie Greene trans, Laughing and Crying (1970), pp. 33.

Such an brief account is, admittedly, a hopelessly shallow exposition of Hegelian philosophy, which cannot be fully explained here.

However, his suggestion of UBI is, in my estimation, far worse.

I need to sit with this essay for longer; it's profound and beautifully written. I think somewhere in it is clarity that I've been looking for around the concept of "work." Which it makes every sense that you would understand where I cannot; although I've had to work my whole life, I've never done physical labor the way you have (and reading your work, I feel I've missed out on something profound). Specifically I've gotten quite caught up on the relationship between the two definitions of work, the one of physical science and the one of labor; I think that this double-meaning is more fundamental than the one "power" occupies as both political power and electricity, because the former translates across languages. This is all a long way of asking you, do you think that fuel does work?

Beautifully judged. As a lifelong Albertan, this hit frigidly home.