Bonnyville, Alberta

Introduction: Objects and Hyperobjects

What is oil?

One might easily fall back upon the scientific definition of oil as a material substance—a flammable liquid composed mostly of hydrocarbons found in underground geological formations. But if by a definition we seek to understand a thing, then this definition fails, as such a reductionist account fails to exhaust all the effects of oil and emergent properties which might arise in certain circumstances and not others. In the thought of Graham Harman, this would constitute the “undermining” of an object—reducing a thing downward to its material parts. Through this, we lose sight of the object. Understanding oil as a liquid hydrocarbon doesn’t give us the tools to anticipate the scope of oil in the modern world.

But, by defining oil by its effects, by what it does, we fall into the other extreme—what Harman calls “overmining,” or reducing a thing upwards to its effects. This approach fails also, given that it neglects the potentialities of a thing. If one accepts that a thing is defined by its effects, then one is forced to bite the Megarian bullet and assert that one is a homebuilder only if and when he is building a home.

We cannot understand oil by looking at a sample of oil because the entity “oil” is something entirely different in character than any localized instance of it. It would be like trying to understand the Black Forest by looking at a single tree, or America by looking at a single street in Philadelphia. Oil, as a totality, has emergent properties which are not observable at the local level.

My analysis must borrow from Timothy Morton and his concept of “hyperobjects,” which he defines as “things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans.”1 Hyperobjects exist, but at a scale so large that it is impossible to point to one and say “here it is.” Where is climate change? Where is the atom bomb? Where is democracy? These things are real, but vast and difficult to pin down.

Oil, for Morton, is a hyperobject par excellence. “Where is oil?” is a sanguine question—it is everywhere and in everything. Relevant to the present analysis, Morton further defines five key traits of hyperobjects: they are viscous, non-local, temporally undulating, phasing, and interobjective.

Viscosity is appropriate here, for oil is sticky, not merely in a literal sense. It attaches itself to us and fills our minds. Oil is not only material, but metaphysical also, or else it would not live within our imagination. As will be revealed through this essay, oil has shaped our collective consciousness in indelible ways. Oil burrows into our lives. It is immensely difficult to free oneself petroleum and its many forms in the modern world. As oil sand scientist Karl Clark used to say, “once the tar sticks to your boots, you can never get it off.”

Oil is non-local in that it is everywhere. There is no place where oil is. It dwells in deep underground reservoirs, in gas tanks of our cars, and in microplastics accumulating in far corners of the globe. Even where there is no oil, oil can exert its might.

Oil does not exist at any given time. It exerts a backwards causal influence in time—the promise of gushing black gold has long enticed wildcatters since the first oil wells drilled in Oil Springs, Ontario. It exerts a causal influence upon the future also, for the effects of an oil economy will be felt long after the taps have turned off. Oil weaves nimbly through time, temporally undulating.

Just as the tides wax and wane, so too does oil phase back and forth. The price of oil rises, at which point it exerts an acute and noticeable pressure, and then it falls, easing us back in to a Lethean bliss. Oil oscillates between the background and foreground, potential and actual, but it is always there, oozing in its protean glory.

But oil demands a conduit—it becomes interobjective, working through other media. It comes in disguised forms. Pipelines are the most conspicuous medium through which oil travels, but in the age of oil, man also becomes a pipeline. Oil works through him, animating him, hiding in him. Philosophy and science declare themselves to be autonomous disciplines which search for truth, but they share a common master. In the age of oil, the activity of thought becomes channeling of materials. Morton writes that “oil and deep geological strata spring to demonic life, as if philosophy were a way not so much to understand but to summon actually existing Cthulu-like forces, chthonic beings such as Earth’s core.”2

Oil has shaped modern Western civilization perhaps more than any substance except steel. It is something so essential to us that we have neglected to examine it closely. Andrew Pendakis has called oil the “ur-substance”3 This is not merely to say that oil has been a useful tool, though this is, of course, true. Rather, oil exerts an omnidirectional influence upon every aspect of our lives.

The notion that we are active subjects, while the world is a passive object, is a modern delusion. A naive anthropocentrism supposes that we are the only causal agents in the universe. Contemporary quantum science already soundly thrashes this view. There can be no stark subject-object distinction, for we are as much objects as subjects. We do not merely shape the material world as we wish, but the material world shapes us in turn. Tools impose upon us the way they ought to be used. We obediently do their bidding. Oil is an firm master, and we are entirely servile.

This essay is fundamentally ontological, seeking to understand what oil is. We do not, however, have direct access to this substance. Another modern delusion is that we can pierce through accident to distil the essence of a object.

Kant rightly observed a yawning gulf between us and the things in the world. The observing subject cannot have direct access to these “things-in-themselves,” but rather imposes his own categories of understanding upon the manifold to interpret them. Kant was, however, only half right. The problem is not only that we lack the tools to reach the things. In addition, the things are shy, refusing to be reached. In Heideggerian terms, objects withdraw from our access.

There is good news and bad news. The bad news is that this makes objects harder to pin down, as they are constantly morphing, changing, hiding from us. As with human interaction, we can never quite tell when someone is presenting their “authentic self” or merely a facade. The good news is that, because objects are active and causal entities, they give us some threads to cling on to, some revealing vestiges, some cryptic riddles for us to solve. Because objects are active, they impress themselves upon us.

Unfortunately, there is more bad news: objects permeate. Especially hyperobjects. It is impossible to see them because we see through them—glasses and contact lenses are dominantly made from plastic. It is impossible to think about them because we think them. It is impossible to speak objectively of oil, for there is bitumen on my breath. There is no way to stand outside a hyperobject when it encompasses all of us. In the case of microplastics, oil is inside of us, and in the case of makeup and lotion, it is on our skin also.

But this might yet be good news in disguise: in the age of oil, self-knowledge constitutes knowledge about oil. Oil reveals itself through its effects on our mind. Self-reflexion, contra Descartes, is not to reason purely, but to empirically observe the self as a microcosm of the world. Our thoughts are not our own. Pure reason is riddled with impurities.

It has been philosophically en vogue for the past few centuries to assert that no two objects can ever touch. Perhaps oil’s hydrophobia is part and parcel of this doctrine. Regardless, it seems in this that we are caught anew in the old Greek debate between the One and the Many, between the continuous and the discrete. Contemporary philosophy often demands that we choose between the notion that everything already exists in an undifferentiated unity, or that there is a gaping lacuna between a multiplicity of insular atoms.

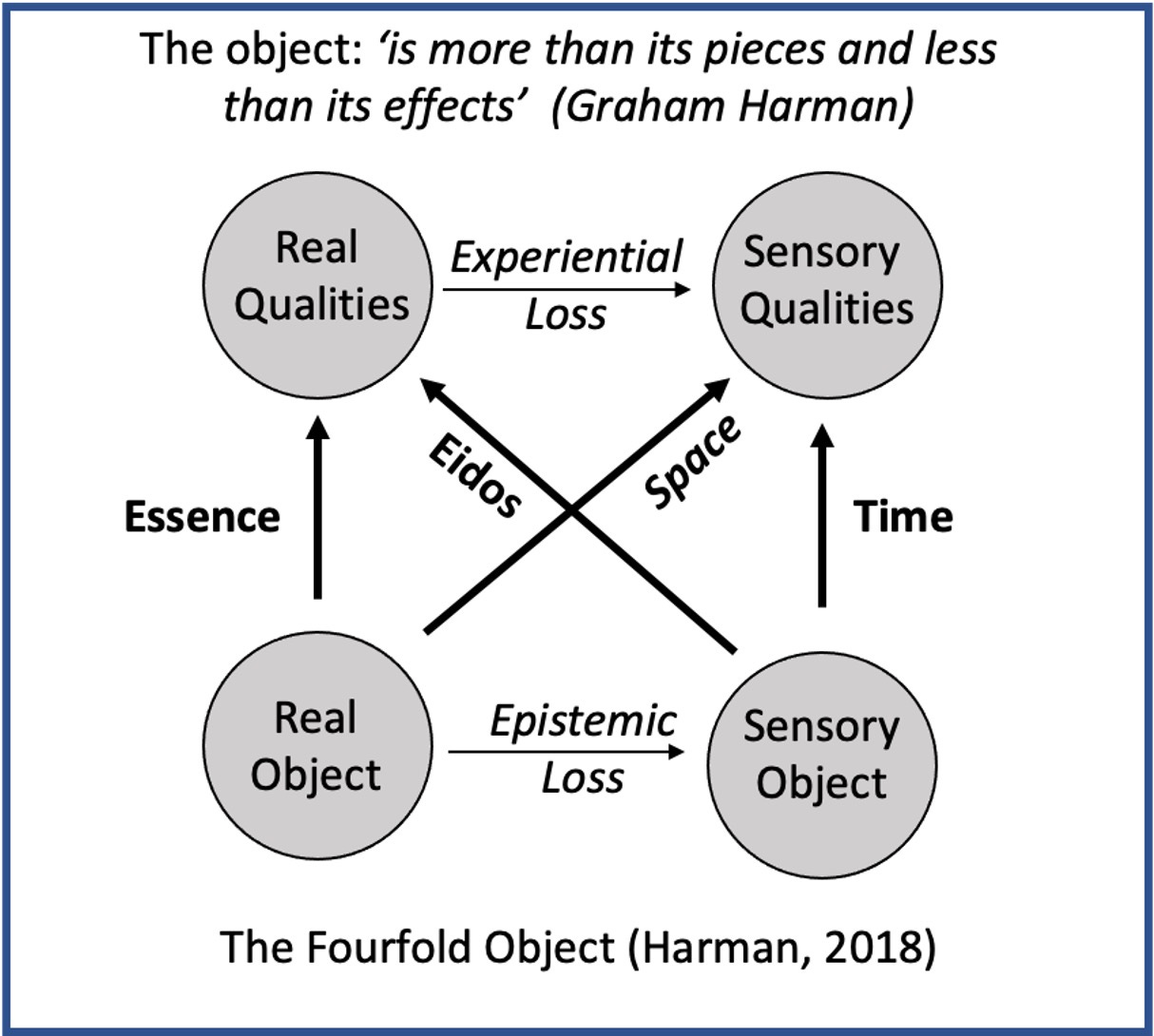

From this dichotomy, a third way opens up: Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), a contemporary philosophical movement spearheaded by Graham Harman. Simply put, it is a school of thought which proposes that objects are real and determinate, that they are causal, but that they are withdrawn from our access, and so our knowledge of them is always imperfect. It introduces a “flat ontology” wherein each object is treated equally, and interacts on an equal plane. Harman writes that OOO

takes the other fork in the road after Kant than the one taken by German Idealism (Hegel, Fichte, Schelling): which eliminated Kant’s things-in-themselves while affirming his prejudice that philosophy must talk primarily about the interplay between thought and world, leaving any object-object interactions apart from humans to the mathematizing methods of natural science. By contrast, OOO endorses the things-in-themselves and asks instead why Kant treated them as the sole and tragic burden of human beings, rather than as the ungraspable terms of every relation, including those between fire and cotton or raindrops and tar.4

Object-object relations, though possible for Harman, can only happen through what he calls “vicarious causation.” This is the idea that objects can interact through the images they present to one another—through their sensual qualities. Causation becomes an aesthetic phenomenon. Essence shines forth in a more literal way than Hegel could have imagined.

Harman writes that “aesthetic phenomena result whenever a wedge is driven between an object and its qualities.”5 That is, through aesthetic phenomena we may trace any qualities presented to the objects which are vicariously interacting therein. However, Harman insists that objects are not identical with their qualities, but have a tense relationship with them. As such, matching things with their qualities, playing philosophical pin the tail on the donkey, is not a fool-proof path to knowledge. The qualities we see are merely those which objects choose to reveal.

Harman proceeds to posit the existence of real and sensual objects, and corresponding real and sensual qualities. Real objects are abstract and metaphysical, while sensual objects are concrete and material. Oil, as a totality, may be a real object, while the crude oil I see before me is a sensual object. The human mind is real, while the body is sensual. Real and sensual objects and qualities are connected and interact in a complex matrix.

Because causality is aesthetic, real objects can only effect change through sensual appearance, and sensual objects can only effect change if they work through the medium of a real object. For instance, metaphor is the linking of two sensual things through their interaction within the human mind. In other words, oil qua real object (read, hyperobject) connects with our minds through the battleground of sensual appearance, while oil qua sensual object (read, instances of oil) is directly present in our minds because we understand their effects on our bodies. Body and mind being inextricably linked means that we may be affected by the entire range of oil’s qualities, both sensual and real.

The present analysis is, needless to say, informed by the Object-Oriented Ontology of Harman and Morton. However, I do have a notable disagreement. OOO posits that direct knowledge about objects is impossible. I argue that knowledge is possible in degrees and in an oblique form. There may be no metalanguage to talk about objects, as we are inside of them, and there may be no thinking about objects, as we think through them. However, there is something deeper than thought or language which is also immediate (without mediation): awareness.

Awareness is deeper than knowledge, for while knowledge comes about through expression, awareness precedes expression. Though our language may be tainted, it can stimulate awareness, as in the Buddhist proverb about the finger pointing to the moon. The finger is not the moon, nor does the finger touch the moon, but it may gesture towards it. The Continental tradition of philosophy mistakes the finger for the moon, and so disparages the finger. This is a grave error, though better than the Analytic philosophers who naively believe that they can hold the moon in the palms of their hands. If we can be aware of the many ways that our thought patterns are shaped, we can begin to counteract those influences. The ideal of knowledge may be an asymptote in that sense, but one which we can approach, at the very least.

The correct method for philosophy, then, might not be proving, but probing. Knowledge cannot come about through literal propositional statements, but if at all, through language which errs on the side of the lyrical and poetic. Koans may be as effective, if not more so, as arguments for achieving awareness. This essay does not constitute an argument about, but a meditation upon oil. Moreover, knowledge is a matter of degrees, and we can never tell exactly when we have fully exhausted an object through enumerating its qualities.

Real qualities are displayed in the battleground of experience, while sensual qualities in the arena of our minds. The domains for understanding become self-reflexion, but also history, where we can locate objects and study their activity over time. Here Heidegger is prescient: Being can only be revealed in time.

To get at the reality of oil, we must attempt to cultivate awareness of it, in the many different faces it assumes—some concrete and some abstract. Oil has both real and sensual qualities, which are identified through introspection and historical understanding. If there is to be a field of petro-philosophy, it can never be divorced from petro-history.

Let us then journey forth, wandering through the halls of history and reflection to discover the many visages donned by this mysterious and protean black ooze.

Oil as Money

If you ask anyone working in the Oil Patch what oil is to them, they will tell you: “oil is money.”

By all concrete metrics, this is true. Oil and gas currently account for 2.2% of global GDP. The industry accounts for 8% of GDP in the United States, the world’s largest producer and consumer of oil, and a staggering 50% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP. Oil and gas provides 55% of the world’s energy,6 and 90% of global transportation energy. $171 billion was invested globally in oil and gas production in 2024. The world economy is inseparably intertwined with oil and gas.

Nor is this trend diminishing, despite the movement towards green energy. Oil demand is projected to rise 23% by 2045, while gas demand is also expected to continue rising through the 2030s.

Canada, alongside Saudi Arabia, is a veritable petrostate. As of 2024, Canadian crude oil exports alone accounted for $134 billion, almost 20% of the country’s total exports. This sum dwarfs every other sector—agriculture, lumber, auto manufacturing, or steel. And that is not even mentioning exports of natural gas and refined petroleum products, bringing the total to $170 billion. We are the world’s fourth largest oil producing country, and Canada’s energy epicentre, the province of Alberta, alone has the fourth largest proven oil reserve on earth.

For individuals, too, oil is where the money is. In Canada, oilfield wages are substantially higher than the national average. Alberta, is per capita the wealthiest province in the country, with the highest median salaries. Everyone knows, if you are badly in need of cash, you go work the rigs.

When I was new to the Patch, a grizzled veteran had warned me: some men become addicted to drugs, some to liquor, some to gambling, some to sex—but in the Patch, the greatest and most destructive addiction is money.

Indeed, some of the wealthiest societies per capita on earth are the opulent, oil-rich kingdoms in the Middle East, with towering skyscrapers, luxury cars lining the streets, and unbounded extravagance. There, too, money becomes an addiction. Oil is money, indeed.

We must be careful not to dismiss or misinterpret this statement. It is not that oil is money indirectly because of the money it generates. It is not that oil is like a currency in the twenty-first century. It is not that oil is a highly valuable substance. Oil actually is money.

This is a metaphor. But a metaphor is not mere fiction. A metaphor only holds weight if it corresponds to the real. “A tree is a duck” is a poor metaphor, yet “oil is money” just works. A metaphor exists in the human mind, which becomes the medium to transmute oil into money. In the framework of vicarious causation, metaphor connects two sensual objects. The metaphor holds if the the one object correctly draws hidden aspects out of the other object. The metaphor “oil is money” evokes a quality in oil which ordinarily goes unnoticed. It it not that oil produces money, but that oil manifests as money.

We can readily see oil at play in the global economy.

In times of stability, we remain ignorant of the bituminous tendrils guiding the flow of global capital. There are, however, occasional shocks which reveal to us that we are at oil’s mercy. The 1973 OPEC oil shocks, when the price of oil rose 300% almost overnight, led to a cascade of price increases, inflation, unemployment, and a global recession. This was only exacerbated by the second round of shocks after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Or, we can look more recently to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russian oil was met with sanctions the world over, leading to high gasoline prices—following suit was high inflation and economic stagnation.

When the price of oil rises, the very foundation of the global economy is shaken. Tremors are felt in all corners of the globe. Aftershocks echo for years after. It is only when something becomes a problem that it becomes conspicuous as an object of inquiry. Only when oil’s effects on the global economy are salient do we recall its omnipresence.

Oil is money.

Oil as Energy

Oil is energy. There is obviously a crude literal sense in which this is true. Oil is a highly energy dense substance, which largely replaced coal as an energy source, after which natural gas supplanted both in energy density and combustion efficiency. Oil is a substance entirely brimming with vitality. It is volatile, eager to ignite. Fuel hydrocarbons are characterized by weaker internal bonds, making them far more combustible. Oil is wild and unpredictable, resisting the yoke of any who wish to control it. Yet one would not perceive such vitality just by looking at this black, lifeless, oozing substance.

There are certain materials for which men will scour the ends of the earth. Prospectors from all over braved the icy winds of the Chilkoot pass for a hand at Yukon gold. Men trained their breath and faced a myriad of deep-sea perils to hunt pearls on the sea-floor. Diamonds, silver, and rubies inspire men’s hearts and minds, leading them on dangerous quests to far-off lands. Such resources contain a kernel of vitality.

Oil is one such substance.

Oil is not necessarily rare—there are dozens of substances more uncommon than oil which men do not expend every effort to find. One might say that oil is merely valuable. But, copper is valuable, and far rarer than oil, yet men do not lie awake at night, dreaming of vast reserves of copper. Oil is highly useful, yes. But so is iron, and yet iron is not likened to gold itself. No, there is indeed something special about oil, irreducible to its value, rarity, or utility. There is an energy inherent in this substance—a fervour it imparts upon the men that seek it.

Oil demands only the most daring, courageous, and worthy men. Early stories of the Canadian Oil Patch recount wildcat drilling rigs operating in the harshest and remotest conditions imaginable, geological surveys wading through the muskeg and snow of the Athabasca Oil Sands, exploration in the Northwest Territories along the Mackenzie River, or even the high arctic, in regions only accessible by helicopter. Globally, we see the same. In the mid-twentieth century, geologists traversed the inhospitable deserts of Saudi Arabia to discover the legendary Ghawar field, the world’s most productive oil and gas field. Men will even go to great lengths for the oil on the ocean floor, constructing monumental offshore oil rigs—incredible feats of engineering—such as at Tiber or Hibernia.

Indeed, the men who hunt for oil are famously some of the toughest and most courageous individuals in society. The archetype of the roughneck is characterized by pure masculine vitality. It is hardly an accident that oil draws these kinds of individuals, for like matches like. Indeed, strong individuals are needed to contain the very oil that brims with energy.

And then, after wildcatting in the bush for months, drilling deeper and deeper into the ground, perhaps even after a dozen or so failed wells, the black gold begins to spring up in an uncontrolled gusher. The potential energy of the pressurized reservoir has become kinetic. Oil has been known to shoot over 200 feet in the air, as at the legendary Lakeview Gusher in California, and at a rate of 18,800 barrels per day.

This reveals a hyperobjective feature of oil—that it exists on a higher dimension than we can perceive. The evidence of this is that oil extends its reach backwards and forwards in time. It is the promise of oil, not tangible present oil, which leads men on these impossible quests. Oil plants the idea of riches in their minds and the spirit in their hearts to seek it out. And, indeed, oil extends its reach far into the future also, as its effects long outlast it its presence.

Moreover, man is not the causal agent in this equation. Man is a mere conduit of oil’s activity. To say that man is the active subject in his search for oil would be like saying that air is responsible for the transmission of sound waves. The air facilitates their travel, but the sound waves are not produced by the air. Man, just like the air in this analogy, is a mere medium. The vitality which fills his heart is not his, but is buried deep beneath the earth.

Oil is interobjective.

In Morton’s terms, oil’s energy phases, oscillating between potential and actual. There are periods boom and bust. The fates of oilfield towns rest upon the whims of oil—whether it reveals itself or lurks underground, whether it floods the market or makes itself scarce. In boom times, oil’s energy is infectious, where Fort McMurray and Grande Prairie positively buzz with activity. In bust times, shutters are drawn and such towns enter a period of hibernation. However, the energy remains constant through this all, merely phasing in and out of existence—here potential, here actual. Only when viewed from a sufficiently high dimension can one see the total energy of the system.

Indeed, the energy from oil is enough to destabilize entire regimes—not through lack, but abundance. The Middle East, the most oil-rich region on earth, is hotbed of civil war, usurpation, regime change, and violence. Trying to understand these conflicts from a top-down political perspective may only reach so far. Perhaps a bottom-up approach is needed—one that begins below the earth.

Oil as Power

The natural correlate of energy is power. The scientific definition of energy is “the ability to do work.” Whereas energy signifies an individual’s ability to do work directly, power consists in the ability to do work indirectly. To exert power is to make things work for you. The social connotations of this formula indicate the political nature of energy. In this way, oil is a kingmaker.

We might ask, is it a mere coincidence that the last region on earth under the control of autocratic kingships is the oil rich middle east? Saudi Arabia, home to the Ghawar Field, the most productive oil field on earth, or Qatar, atop the North Field, the largest gas field on the planet, are oil rich monarchies, as are the UAE and Kuwait. Iran, despite its vast oil reserves, is hardly a prosperous nation, having among the lowest GDP per capita in the world—and yet, it is still highly centralized and autocratic. Whoever controls the oil controls the state. While many of these countries have had longstanding kingships dating back centuries, the major oil discoveries in the 20th century accentuated the trend of centralization so that, today, the flow of oil is tightly controlled by the government in each of these countries.

The precise relation between oil and power cannot be proven, but we may be allowed to probe.

Indeed, in North America, oil exerts a salient political influence also. In both Canada and the United States, oil and gas lobbies are immensely powerful entities—and proportionately more so in Canada, where the interests of the “oil men” of Calgary form the backbone of the Conservative Party of Canada, one of the two major political forces.

When the political sphere alone is insufficient to push forth a policy vision, warfare must be conducted. In Clausewitz’s classic dictum, war is only “policy by other means.” In the 20th century, the developed world began to understand that the key to modern warfare was petroleum.

The First World War was characterized by grueling attrition. Trench warfare predominated, with an obdurate Western Front and frustratingly slow progress for advancing forces. The Second World War, on the other hand, was a war of intense and fitful mobility, with pincer attacks, rapid maneuvers, and constantly shifting battle lines. The difference between the two wars was not a difference in grand strategy, but a difference in technology. Namely, WWII took the form that it did because of oil.

writes, “The Second World War . . . was a war of motion, which spanned far greater distances across unprecedentedly large theatres of operation. This was a conflict fought with oil, over oil, and was, in part, decided by oil.”7The crux of the war was tanks, planes, and ships—all of which required great amounts of fuel. The success of each side was contingent upon the procurement of fuel. The key struggle the Axis powers faced was their lack of access to oil.

As the great American general George Patton famously declared, “My men can eat their belts, but my tanks have gotta have gas.”

The Japanese expansion in the Pacific theatre veered south, rather than eastwards, primarily to secure the oil reserves in the Dutch East Indies. Japanese expansion stopped because of the difficulties obtaining ample fuel for a decisive naval offensive. When the balance of power shifted in favour of the Americans, the Japanese lacked the mobility to respond because of, again, oil troubles.

Many remark on the striking tactics employed by the Japanese military during the war—not least of which was the famed “Kamikaze” attack, where an explosive-laden fighter plane would crash into an enemy naval vessel on a suicide mission. While this tactic was partly a product of Japan’s intense honour culture, it was equally born of a practical concern: if you sacrifice the plane halfway through the journey, you only consume half the fuel.

Oil was no less decisive in the Western theatre. Hitler’s grand strategy, long subject to ridicule, makes far more sense when one understands the decisive nature of oil in the conflict. Hitler’s disastrous invasion of the Soviet Union was a necessary decision, given that Nazi Germany had chronic fuel shortages due to a lack of access to oil. His goal on the Eastern Front was not solely to seize Stalingrad in a grand symbolic victory—it was more so to secure the oil fields of Grozny, Maikop, and Baku. In a letter to Mussolini, Hitler wrote that “The life of the Axis depends on those oil fields.” As early as 1942, he wrote “Unless we get the Baku oil, the war is lost.”8

America, on the other hand, had a booming oil and gas industry, with some of the most advanced refineries in the world, as well as plentiful domestic supply. Indeed, the Allies won the war not solely through technological innovation, strategy, or military might. They won it in part because they had the oil.

Having oil is equivalent to having power. It is not merely that oil leads to power. Oil is power. Namely, there is a power to effect change on a global and monumental scale inherent in oil and gas—the power to move ships, to fly planes, to maneuver tanks, and win wars, but also the power to build and sustain a country.

Oil as Freedom

Oil, insofar as it is money and energy, empowers both an individual and society to do things. This is power, and a correlate of power is freedom.

There are two kinds of freedom: negative freedom and positive freedom. Negative freedom is the absence of external restriction, while positive freedom is having the means to pursue one’s own goals. Oil not only bestows these freedoms upon man—oil is concomitant with them.

There is nothing more indicative of this than the invention of the automobile. Before Ransom E. Olds invented the assembly line in 1901 and Henry Ford’s Model T—the first peoples’ car—was unveiled in 1908, most people lived their whole lives within a 25-mile radius. Any venture outside that radius was at the mercy of either public transportation or nature. Within a short span of time, everything changed. The Model T sold marvelously, achieving an economy of scale so that the car became ever cheaper and accessible to the common man. With this boom in automobile sales followed a campaign of road construction to connect the distant frontiers of the youthful North American continent.

Freedom of movement was achieved on a scale never before seen. Whereas before the turn of the century, men were tied to their provincial attachments—to their city, their family, their home—the mass distribution of the automobile enabled society to become mobile and agile. Man could forsake his parochial attachments to boldly forge a new identity on the open road. The automobile became emblematic of American freedom and democracy. The open highway presents man with a perfect image of negative and positive freedom—freedom from what is behind him, and freedom to venture forth towards what is ahead. At the heart of this revolution in transportation was oil—in the asphalt which webbed the country, in the fuel tanks of each Model T Ford, in the lubricant which allowed their engines to run smoothly.

America was founded upon democracy and liberalism, yes. But those values had yet to be fully unfurled in history. Until the mid-twentieth century, America was yet a democracy for the few. Women and minorities gained the vote gradually, in direct proportion as the automobile made individuals acutely aware of their new freedom. Whereas movement was once a luxury, it was now a commonplace. The automobile had levelled society, making all hierarchies—of race, sex, and class—contemptible and undemocratic.

Energy produces abundance, which raises incomes and perceptions of self-worth. It is easy to lord over a destitute people, but difficult to rule a people that bursts with vitality and confidence, who understand their freedom and possess the means to assert it. It is no wonder that tyrannical regimes such as China and Iran are required to deliberately keep their people in poverty in order to retain control. More specifically, they are required to restrain the flow of oil and the distribution of energy.

When a king possesses oil, his license knows no limit. When a people possess oil, no sovereign can restrain their liberty.

Sheena Wilson, Imre Szeman, and Adam Carlson write, in the introduction to Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture, that

The verities and pieties of liberal political philosophy were imagined against the backdrop of a world with ever-expanding energy resources. In a world in which energy will no longer be so abundant, we now have to revisit and reimagine our energy intensive freedoms.9

And they are correct. Freedom is energy intensive, for oil produces freedom. Should we ever hit peak oil (as we were supposed to many times), then we can expect a radical curtailment of freedoms, a decline in democratic spirit, and a political freefall towards tyranny. In an age of oil scarcity, the few who control the remaining supply will effectively rue the world. Oil grants, and then rescinds, freedom. Oil giveth and oil taketh away.

Rights are only theoretical justifications to wield the power to do things. The theoretical, however, only applies where the power actually exists. As such, it is not God, nor the state, which confers rights upon man—it is the material conditions. In this case, it is oil.

Thinkers such as Rousseau, Locke, and Paine considered human rights to be inalienable gifts from God. But they just missed the mark. In truth, rights are alienable gifts from oil.

Oil as Plastic

It is in the form of plastic that oil reveals itself as ur-substance, something so ubiquitous in modern society that we hardly take note of its presence.

has called it the “Everything Thing.” Though only 4-8% of crude oil globally is refined into plastic, it has arguably had the most far-ranging reach of oil’s many faces.It has been said that, for something to happen, it needs to happen twice. Plastic, incidentally, was invented three times before someone saw a use for it—in 1894, 1930, and 1933. The first petroleum-based plastic invented was polyethylene, which remains the most common variant of plastic to this day, found in our plastic bags, plastic wrap, and plastic bottles.

Plastic is so durable because each molecule is a long, tangled chain of hydrogen and carbon atoms, whose interconnectedness fortifies the compound in a dense tapestry while keeping it pliable.10 This multifaceted material is called the “Everything Thing” for good reason—you can, and we do, use it for everything. Take a moment and look around you. I would bet that each and every reader can locate a nearby object made of plastic. Indeed, there is doubtless plastic in the device on which you are reading this article.

Plastic is in everything. As such, we cannot escape it. We cannot see outside of it, for everywhere we look, we find it. Plastic obstructs all five senses. It is on our skin, in lotions, makeup, and body enhancements. It is in our eyes, as contacts and lenses. It is in our breath, with microplastics hanging in the air and entering our lungs. It is in our mouths, in chewing gum or the traces of plastic food wrap. It is in our ears, in headphones, earbuds, hearing aids. Not only that, plastics are in our body—plastic’s longevity makes it a useful material for bodily implants such as knee replacements and artificial limbs. Even the stents that keep blood flowing are increasingly made from plastic.

Plastic is even present in our most intimate moments. The skin of the condom, the lubricant on its surface—oil is present. In those rare moments of sexual elation, we might naively think that we escape the physical realm for a rare moment and tap into something divine. However, these moments are dictated by, and contained within, oil, all the same.

How can we feel plastic when it already coats our skin? How can we see it when plastic is in our eyes? How can we smell, taste, or hear it when it blocks our orifices? How can we speak of plastic when it is on our breath? How can we isolate plastic to study it when it is literally everywhere?

But not only that—there is something far more concerning. The list above featured plastic items which we can identify—plastic items which are more or less discrete. But this is a manufactured illusion to disguise plastic’s true nature. Just as oil seeps, sticks, and infests, so too does its scion. Only, plastic is far more subtle. It works its way through nature and society in the form of tiny particles which gradually build up until they are detectable everywhere—microplastics. As the Sorites paradox asks how much sand it takes to make a heap, we are left wondering how many microplastics need to build up to have a tangible effect. As it stands, we are finding more traces of them every day—and discovering the sordid consequences.

Plastic’s greatest virtue is also its greatest curse—it never breaks down. Just as oil takes geological timespans to form, plastic takes great timespans to decay entirely. Polyethylene can take up to 500 years to decompose. Until it does, it merely breaks down into smaller and smaller particles, which settle all across the globe. There are microplastics deep in the ocean, and even at the peaks of mountains. They accumulate at every trophic level, meaning that by the time meat or vegetables reach our dinner plates, microplastics are concentrated.

Microplastics are in our bloodstream. They are in our brains. There is budding evidence that they are carcinogenic and cause reduced male fertility. Microplastics have infiltrated our minds; they have infiltrated our bedrooms. They are in our thoughts—they are prior to our thoughts. Microplastics are the omnipresent specter haunting our rivers, our forests, our food. You cannot even think about plastic, let alone speak of it, because plastic is in our brains. Our thoughts are plastic, our dreams are plastic, our desires are plastic.

Hyperobjects are viscous: they stick to us. Hyperobjects exist on timescales which dwarf the human life cycle. Hyperobjects seldom work directly, but are interobjective; they wear many different masks. It is no accident that plastic is the material par excellence for fabricating disguises—plastic is already a disguise for oil. Morton writes, “In some sense, modernity is the story of how oil got into everything. Such is the force of the hyperobject oil.”11

However, plastic has not only provided a new use for oil—it has created an entirely new psycho-social condition: plasticity.

With a material as infinitely malleable as plastic, we begin to see the world as infinitely malleable. We begin to see ourselves as infinitely malleable. Plasticity is characterized by malleability. Plastic, after all, literally means mouldable, derived from the Latin plasticus. Plastic shows us our unbounded power to shape the world as we please. This attitude extends indefinitely, breaking down barriers, resolving contradictories, and merging opposites. We are taught that we can be anything we want to be.

Petro-historian

writes,Plastic invaded material life utterly and became a cornerstone of the ideology human exceptionalism that is necessary to justify the degradation of the ecosphere. It is infinite in its potential to realize human fantasy: material doesn’t have to look like itself anymore. Here we have a thing that would never exist but for industrial chemistry. What gets lost in this plastic utopianism, on both the consumerist and environmentalist side, is plastic’s origins in petroleum.

The song “Barbie Girl” by Aqua sings mockingly of this condition of plasticity:

I’m a Barbie girl, in the Barbie world

Life in plastic, it’s fantastic

You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere

Imagination, life is your creation

The song emphasizes feminine plasticity, specifically through the eternal male desire to shape women as they please—the eternal recurrence of the Pygmalion myth. It is fitting to note again the high plastic content in most women’s makeup. The condition of plasticity enhances the male capacity for fantasy, while women use plastic in attempt to realize these fantasies.

Nor is the full weight of a plastic condition borne by women alone. Rather, plastic inherently feminizes when it uses someone as a host. Andrea Long Chu defines femaleness as “any psychic operation in which the self is sacrificed to make room for the desires of another.”12 If this is the case, then we are all females in the face of plastic. This is not merely metaphor; insofar as microplastics have been demonstrated to act as endocrine disruptors, their presence in the male body can mimic the presence of estrogen.

Plasticity extends to the realm of ideas. In a plastic age, binaries dissolve, as the barriers between them appear malleable. Man becomes woman. Falsity becomes truth. Other becomes self. Divine becomes profane. Up becomes down. The discrete dissolves into the continuous. Borders fall. Identities blur. Class and caste mix. Aporia is resolved. Idealism runs rampant, while realism falls out of fashion. Society becomes polymerized. All descends into Dionysian flux.

In this condition, even art becomes plasticized. Before the age of oil, artworks were prized and unique. In the 20th century, however, art became mass-producible. As the price of producing artworks fell, they became cheap. New techniques, such as lithography and silkscreen printing allowed for the production and reproduction of images with ease, both empowering the artist to shape his artwork in myriad ways, but also devaluing artistic technique in the process. Rather than rendering art obsolete, many artists embraced a newfound cheapness and malleability in their artworks. This manifested in the Pop Art movement, with Andy Warhol as its figurehead. Warhol’s works embrace commercial imagery and kitsch, as in his famous Campbell’s Soup Cans. Such art is fundamentally plastic, malleable and mass-produced.

Not only art, but philosophy and the sciences came to embody the condition of plasticity in the twentieth century. It is thus revealed that material conditions furnish us with ideas and patterns of thought. When a scientist speaks, he is channeling the oil beneath the ground, in its various forms. When a philosopher speaks, plastic particles emanate from his mouth. Intellectual trends take hold if and when they harmonize with concrete circumstances.

We are taught that the world is our oyster, yet we are dwarfed by the world. This paradoxical state is emblematic of a plastic condition, for plastic empowers us, yet controls us. Plastic serves as a mighty and multifaceted tool, but it is a Faustian bargain; the plastics that we use will never go away, but will haunt us for eternity.

Plastic is cheap. Nylon stockings readily tear. Polystyrene packaging is peeled away and discarded. Single-use polypropylene straws pile up in the world’s wastebaskets. The abundance of plastic cheapens our lives. Moreover, the disposability of plastic evokes the present, the temporal. And indeed, plastic embodies fakeness as well.

It is only when things become cheap, fake, and evanescent, that there arises a crisis of value. This is hardly equivocation—the value of the objects around us correspond to our ideas of value. In a plastic age, men long for what has eternal and universal worth. They must peel away the celluloid film to find what is real.

It is in plastic that oil is revealed as a trickster spirit—it is never what it seems. It lurks in every corner. It infiltrates our minds. It hides behind a mask. When oil is plastic, it becomes even harder to pin down, just as old man Proteus changed shape every time he was cast in a net.

Oil as Lubricant

Oil is a lubricant—it makes things work smoothly. WD-40 reduces the friction on squeaky hinges. Engine oil keeps the parts under your hood ticking in perfect clockwork. Lubricant has allowed revolutions in the speed and scale of machinery. This material fact, moreover, suggests a metaphysical counterpart.

Mark Simpson diagnoses society at large with the oil-induced condition of lubricity:

Lubricity offers smoothness as cultural common sense, promoting the fantasy of a frictionless world contingent on the continued, intensifying use of petro-carbons from underexploited reserves in North America. It thereby contributes to the contemporary mobility regime that, idealizing smooth flow, mystifies so as to maximize the violent asymmetries of movement and circulation globally.13

Oil has carved out a system of trade and transportation networks to facilitate its smooth flow the world over. Each of the globe’s inhabited continents are home to a map of webbed pipelines carrying their sweet bounty to and fro to appease our insatiable appetite for energy. Oil and gas tankers cross the world’s oceans on precise schedules to deliver their freight. Our global trade networks are predicated upon the smooth flow of oil.

Oil, in turn, powers the transportation of myriad other goods by earth, sea, and sky, enabling international trade on a scale never seen before. Indeed, globalism is only a possibility in the age of oil. Revolutions in logistics have allowed for goods from the corners of the globe to reach us almost instantaneously. Bananas grown in Central America can be on our shelves in a week. Our supply chains are so efficient that it is cheaper to source most manufactured goods from elsewhere than to produce them domestically.

This state of affairs has imprinted certain thought patterns upon our minds. The advent of plastic has ushered in the condition of plasticity; so too has lubricant ushered in the condition of lubricity.

There arises the expectation of frictionless and instant delivery. Men begin to believe in smooth flow from point A to B, delivery within three to five business days. The world begins to seem smaller, more accessible, readily traversable. Indeed, lubricant imbues the world with speed. Everything happens quickly and easily.

A lubricated world is a well-oiled machine. With the advent of lubricant, machines could suddenly run so smoothly as to mirror the seamlessly functioning systems of the natural world. It is, then, no surprise that machine metaphors have taken over philosophy and science in the twentieth century, albeit with some impassioned resistance from Whitehead. Life and nature, wanton and wild beasts, came to be understood through machine metaphors, reducing interconnected systems to a series of atomistic parts. Human society, once seen as a similarly unpredictable phenomenon, was put under the careful eye of a new field of study—political science—which attempts to understand society by isolating its component parts to study how they work together. This approach—breaking wholes down into their parts, studying the parts, and reassembling them back into a whole—is akin to a mechanic disassembling and reassembling an engine. Such an analysis is only possible when life is viewed through the lens of lubricant.

As lubricant facilitates travel from locale to locale, it banishes mediation altogether. Immediacy prevails. This physical fact has a metaphysical counterpart. Whereas plasticity imbues our minds with an malleable ontology, lubricant facilitates rapid interchange between poles. Opposites turn over into one another rapidly, oscillating back and forth as in an engine’s rapid motions. One appears imposed upon the other as in a mental zoetrope, occupying a superposition. In a well-oiled machine, it may appear as if opposites can coexist. Oil facilitates continuous sensory overload—everything, every place, and every time, may be present at once. What, then, happens to the law of the excluded middle?

Plastic makes contradictories malleable, whereas lubricant dissolves them altogether. Lubricant allows a man to hold two opposed ideas in the palm of his hand. Formal logic has followed suit, like a dog following his master. Para-consistent logic has caved into the condition of lubricity, with thinkers like Graham Priest devising frameworks in which logic can accommodate, and not reject, contradictory statements. It is no accident that the West has seen a rising interest in Buddhism—the religion which rejects difference and embraces the sublime oneness of Nirvana. The Buddhists hardly suspected that Nirvana would be a puddle of oil.

However, this whole physical and metaphysical machine only keeps ticking with an ample supply of lubricant. Where the lubricant runs out, the whole thing falls apart.

What has recently been revealed, by the world economy shutting down because of Covid-19, is that these highly lubricated trade networks, and their corresponding mental matrices, are so very fragile. As in the Jewel Net of Indra, each node shines through every other. A slight modification in one node affects each other entangled node simultaneously. A single shock can set of a chain reaction. The scarcity of a single input makes all the downstream manufactured products dearer. The shock of a disruption in our supply chains brings us out of our torpor, directing our attention to the very foundation of our modern trade network, which is lubricant.

Heidegger certainly has a word on this.

In his famous “tool analysis” (Being and Time, I.3.15-18), Heidegger brings our attention to the objects in the world and our mode of understanding them. Our natural instinct is to examine things instrumentally, i.e., what something is for. To use Heidegger’s terms, we understand things as ready-to-hand, and take them for granted as such. However, we do not find the true Being of an object in this manner. He writes, “The peculiarity of what is proximally ready-to-hand is that, in its readiness-to-hand, it must, as it were, withdraw in order to be ready-to-hand quite authentically.”14 The concept of withdrawnness is crucial to the OOO enterprise, supposing that there is some authentic essence to objects which they choose not to show. Viewing things instrumentally prevents us from correctly understanding them.

It is when this readiness-to-hand falls away that we can examine an object more closely. Specifically, it is when something breaks. Heidegger continues,

We discover [a tool’s] unusability, however, not by looking at it and establishing its properties, but rather by the circumspection of the dealings in which we use it. When its unusability is thus discovered, equipment becomes conspicuous. This conspicuousness presents the ready-to-hand equipment as in a certain un-readiness-to-hand. But this implies that what cannot be used just lies there ; it shows itself as an equipmental Thing which looks so and so, and which, in its readiness-to-hand as looking that way, has constantly been present-at-hand too. Pure presence-at-hand announces itself in such equipment, but only to withdraw to the readiness-to-hand of something with which one concerns oneself-that is to say, of the sort of thing we find when we put it back into repair.15

When an object breaks, it becomes conspicuous—its readiness-to-hand is replaced with presence-at-hand. In such a state, the object ceases to withdraw totally, but offers us a genuine glimpse into its Being. A broken hammer draws our attention to the tool in a way it never would were it in perfect working condition. When the hammer is fixed, its presence-at-hand withdraws, and instrumental reason begins to dominate once more.

We see the presence-at-hand of oil shine forth on a global scale whenever oil stops working.

The disruptions to the global trade network as during Covid-19 brought our attention to our supply chains. The 1973 oil price shocks brought our attention to oil’s role in our monetary system. Paradoxically, shortages of oil bring our attention to its presence. It is in these disruptions, and these alone, when we are shaken from a petroleum-induced stupor and catch a glimpse of oil’s nature and the condition it has impressed upon us.

When oil works for us, we may puff ourselves up with all kind of arrogant witticisms—technology is just a tool to be used for good or evil; we are masters of our own destiny; man is born free. In reality, our tools dwarf us. Occasionally, oil feels the need to humble us, to remind us of our servility.

Oil as Void

But look at us—we have waded deeply into a realm of abstractions. Perhaps we have lost sight of ourselves and the matter at hand. Or perhaps not. We have only been probing, after all.

We have certainly proceeded from oil’s most concrete qualities to its most abstract—in OOO terms, from its sensual qualities to its real qualities. Let us return to the sensual once more. Let us look at oil.

What is most salient of all? It is black—the shade that swallows all colour. There is an important metaphor here (and let us not forget the causal nature of metaphor). Oil is black—a great yawning emptiness—but because of this, it contains everything.

Oil is a primordial void—the nothing from which everything comes.

Perhaps oil is a contradictory substance, containing vast multitudes. Hyperobjects, for Morton, not only can be contradictory entities, but are of necessity.16 An object can contain its opposite, but retain its essence. It is acceptable to say that oil is itself and everything else. It is acceptable to say that oil is not oil. In this way, oil is a paradigm of a hyperobject: it sticks to us, yet slips through our fingers. Our meagre tools of reasoning are futile when attempting to pin down this multifaceted substance. We may be able to detect traces of its essential features, but attempting to define oil or fit it into our categories of reasoning is a fool’s errand.

In the murky depths of oil, logic is rendered impotent. We see traces of this in the conditions of plasticity and lubricity above the earth. This suggests that the underworld, whence oil springs up, should be a place philosophers fear to tread. We can never understand oil. All we can do is channel it.

Oil is not only a void sensually, but ideally also. It swallows up men and spits out chaos. The energy it produces only ushers us along towards entropy. Paradoxically, the more energy we expend to resist entropy, the swifter we bring it about. It is a black hole, defying everything we previously understood about the world. It has upended the natural order, and ushered in a new and uncanny civilization. We live in the age of oil not because we have oil, but because oil has us firmly in its grasp. There is no colour oil could possibly be besides black.

Andrew Pendakis writes,

We are witnesses, hyper-witness to this accidental essence called oil, this directly effective cause that is also the most Heideggerian of metaphors, a substance literally composed of death and time.17

Yes, the metaphor is almost too perfect. The oil in the ground is literally formed from life, compressed over tremendous timespans. It is made of hydrocarbons—the self-same particles that make life on earth possible. It contains both life and death. In a ravaging irony, DNA, the blueprint of life, is a polymer, just like plastic.

Oil evokes long time-scales, but also instantaneity. Oil stews for entire geological ages before spurting to the surface in a sudden burst of vitality. Plastic, which is used and discarded without a second thought, outlasts us. Oil contains the trivial and profound, the new and the old, all at once.

This makes for a truly monstrous entity, a leviathan that swallows worlds. In the Bible, water functions as a recurring metaphor for chaos. Oil could serve just as well for the same.

Oil is a terrifying and haunting entity. Environmentalists isolate oil as the paradigmatic villain of the modern world. Its name is invoked with fear and loathing. Oil corporations are treated as evil incarnate, perhaps even more so than big pharma and big tobacco. This fear is entirely justified, but for reasons besides those which environmentalists parrot. Whether climate change is happening or not is ultimately irrelevant. Oil ought to inspire existential dread regardless. The focus on climate change obscures the true nature of oil, whose far-ranging effects are far more diverse than merely raising global temperatures. Oil dictates the rhythms of modern life. It has the power to destroy us far sooner than its tertiary effects via a climate catastrophe.

There are other industries with significant carbon emissions, such as steel, coal, lithium, forestry, or agriculture. Yet, there are no movements called “Just Stop Lithium” or “Just Stop Steel.” Rather, “Just Stop Oil” is the movement with die-hard activists, willing to deface Van Gogh’s Sunflowers with cans of tomato soup, spray paint Stonehenge orange, or use concrete epoxy to glue their hands to major German expressways. These are rabid expressions of a deep understanding that oil is terminality. Such stunts are born of animals who sense that they are cornered, who are willing to fight with tooth and claw to resist a dire dire fate. Little do they know, the very means by which they stage these stunts are petroleum based—both the epoxy they use to glue their hands to roadways and their orange spray paints come from oil. We can’t just stop oil. No one can.

We have long passed the event horizon. Every time we struggle against the force of oil, we are only brought closer into its orbit. Resistance to oil requires oil. It is the void that swallows us whole. Any attempt to escape is futile—like quicksand, the more urgent our fits and starts, the faster we are sucked down into the depths. We are already inside oil, just as oil is already inside us, in a perverse symbiosis. All that is left is for us to rage at the dying of the light.

At least the blue-haired activists somewhat grasp this, if for the wrong reasons. Their approach is more honest than to pretend that nothing has changed in the age of oil.

We would do well not to deny oil its rightful power, for it can be a cruel master if not placated. As Nietzsche writes, “when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.”18

Conclusion: Awareness and Humility

But then where do we stand—we who are in oil and whom oil is inside? What is science? What is philosophy? Do we stand a chance at finding knowledge, or will that slip through our hands also?

Perhaps we ought to let go of this fixation on knowledge. We may do well to set our sights lower at a more tangible, and perhaps more useful goal: attaining awareness.

There is a great confluence of forces which pull our thoughts one way and another. The only way to escape this—if we are ever able—is to attain awareness of all these forces. When we are aware of the way in which technology, the environment, our relationships—even metaphysical forces outside our scientific ken—influence our thought patterns, we may be able to counteract them. Perhaps only in this state of keen and widespread awareness will the truth dare reveal herself.

OOO gives us a path to seeking this awareness, given that real objects exert influence on our minds through our bodies, while sensual objects exert influence on our bodies through our minds. Man is the microcosm of the macrocosm. Through an inward turn, we may peer into the world around us.

Philosophy should adopt the much more humble goal of attaining awareness of these chthonic forces that pervade our environment. The philosopher becomes a medium who channels these forces and gives them a human voice. This becomes the distinct activity of philosophy, only because other disciplines take methodology and epistemology for granted, forging boldly ahead in their search of knowledge. Philosophy is unique in questioning its own first principles.

What sets a man on the path towards awareness is no special piece of knowledge (how ironic that would be)—rather, it is a particular virtue: humility. This is the humility to admit that our thoughts are not our own, the humility to reject “creativity” and admit that we are only ever channeling forces greater than us. It is humility that leads us to question the very tools we use in this vain search for knowledge. Humility is the understanding of our fallibility, combined with an eagerness to improve. It is a precondition to any meaningful understanding.

Arrogance is the condition that stops a man from finding the truth. An arrogant man, who clings to his beliefs as golden idols, who reveres his own cognitive equipment—falls flat. Awareness eludes him.

This understanding of philosophy is hardly new. It is not “Postmodern.” In fact, this is a very ancient view from which we have strayed. This understanding of philosophy dates to the very man who inaugurated philosophy as a discipline—Socrates.

In Plato’s Apology, Socrates is found making a defense speech to an Athenian jury, as he is under charge of corrupting the youth, denying the gods, and inventing new gods. Many of the arguments he uses to refute these accusations are strange and unpersuasive to the jury, but perhaps none more so than his claim that his actions were not his own, but were instructed to him by a daimon—a lesser divinity—whispering in his ear.

It wasn’t Socrates’ fault that he frequented the agora, questioning men about their deepest beliefs—his daimon told him to! And would it not be impious to deny such divine commands?

The jurors were not convinced. Socrates was condemned to death.

But Socrates was honest in a way that the jury was not. He was aware that his thoughts were not his own. It is fitting, moreover, that the first man to be aware of this was also a paragon of humility, admitting that he knew nothing at all about the most important things. It was not knowledge he sought, but awareness, which he called self-knowledge. I only use “awareness” and not “self-knowledge” because, since Socrates’ time, we have discovered the porous boundaries of the self and the dubious status of knowledge.

Oil is my daimon. It is yours also.

We have a multitude of daimons that haunt our minds. The task of philosophy is to reveal them for what they are, to pick apart the ways they influence our thoughts, and to bring others into this state of awareness. Such a task is necessary before we even think about looking for knowledge.

All the great epic poets in Western history invoked the muse before beginning their verse. They were aware that artistic and philosophical production is a matter of channeling forces greater than oneself, while the poet is merely a passive receptacle.

Oil is my muse.

A man may think that he is safe from oil in the sanctum of his own mind, but he is not. Each man must ask himself how oil has shaped his thoughts, his personalities, and the ideals he holds dear. Such an inquiry will reveal that this black primordial goop indeed holds illimitable dominion over all.

Morton, Timothy, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World (2013), pp. 1.

ibid, 175.

Pendakis, Andrew, “Being and Oil: Or, How to Run a Pipeline Through Heidegger” in Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (2017), pp. 377.

Harman, Graham, Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything (2018), pp. 255-256.

ibid, 149.

Conway, Ed, Material World (2023), pp. 319.

ibid, 336.

ibid, 337.

Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (2017), pp. 7.

Conway, 354.

Morton, 54.

Chu, Andrea Long, Femaleness (2019), pp. 11.

Simpson, Mark “Lubricity: Smooth Oil’s Political Frictions” in Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (2017), pp. 289.

Heidegger, Martin, Macquarie and Robinson trans. Being and Time (1962), I.3.15, pp. 99.

ibid, I.3.16, 102.

Morton, 78.

Pendakis, 387.

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Walter Kaufmann trans. Beyond Good and Evil (1966), §146.

Great essay. I'm especially intrigued by the lubrication section. If oil is needed for two contradictory machine parts to work together, then what is needed for a person to hold two contradictory thoughts together? In other words, what is the mental equivalent of lubrication/oil? I've been pondering this since reading your essay, and I think the answer might be: metaphor. Within the medium of metaphor, thought's contradictory gears don't grind against each other. Metaphor deconstructs meaning into pre-categorical elements much like oil is matter reduced to pre-categorical, undifferentiated stuff. Metaphor then fills in the gaps between thoughts, letting contradictions coexist. And if you want to get really weird with it, I think that, if you take these ideas to their logical conclusion, you end up with the thought that oil is the intuition of the Earth --its accumulated biological history compressed into intuitive form -- just as metaphor is the intuition of the mind.

Wow. Turn this into a book. I can’t imagine any publisher turning this down.