Cold Lake, Alberta

When I observe the men of the Patch, I see a strange rift between form and content. There is a glaring dissonance between their words and their actions. The West has a reputation for being the most patriotic region in the country, yet many men want Alberta to be swallowed whole by the Leviathan that is our southern neighbour.

They fly Canadian flags, yet yearn for subsumption into the American Empire.

They scorn woke revisionist historicism, yet immolate their own history.

They scold immigrants for not wearing poppies, yet betray this country for which their ancestors fought.

Reason fails to bridge this rift. How can a place be socially conservative, yet reject its own history? How can men be patriotic while salivating at the thought of annexation? How can men speak so strongly and boldly, yet be too cowardly to carry on the great tradition passed down to them? Trump speaks of making Canada the 51st state, and the men of the patch welcome it. Approximately 20% of Albertans desire this possibility. When I speak to them about the subject, it seems even higher.

What is this strange ideological concoction in the men of the Oil Sands? As it is tangled in a web of contradiction, it can hardly be called a political ideology, which would be rational and self-consistent. Nor is it necessarily an expression of pragmatic self-interest—it is well documented that political beliefs rarely reflect genuine self-interest. There must, however, be a mechanism by which political beliefs are adopted by particular populations en masse. There must be a cause. There must be consistency. It all seems so natural—the lifestyle, the way of this land. Let us probe further.

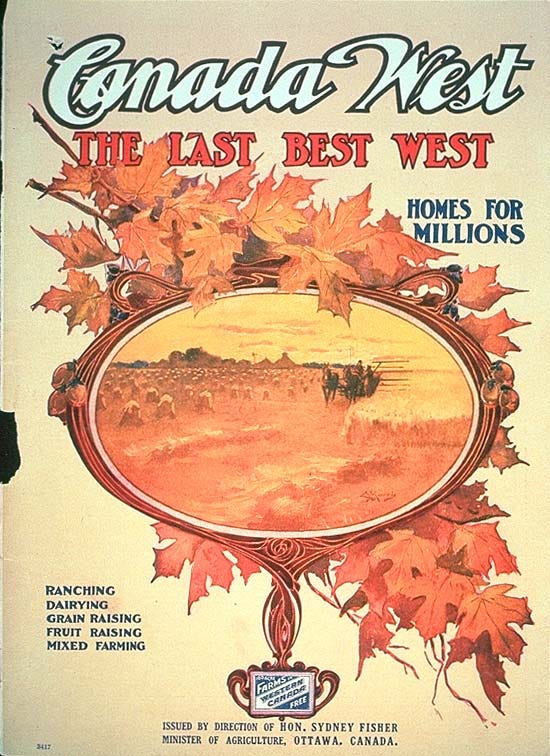

Alberta has been termed the most “American” province within Confederation, and for good reason. Since even before its inception as a province, the first major wave of immigration to the prairies west of Manitoba was from Americans eagerly seeking farmland in the “Last Best West.” While few contemporary Albertans are descendants of pure American stock (if there is such a thing), this wave of ~600,000 Americans to Saskatchewan and Alberta has had a lasting effect on the beliefs and spirit of these two provinces. This is in distinction with Manitoba, whose first major wave of immigration consisted of British Ontarians—helping shape its moderate and pan-Canadian disposition.

Albertans Conservatism thus has a distinctly American ethos. Albertans, of all provinces, are the most distrustful of the federal government, most likely to support loose gun laws, and the most resistant environmentalist policies. They support more provincial power to prevent government overreach. On social issues, ranging from abortion rights to medically assisted death, they are more conservative than the rest of the provinces. This makes them a black sheep within Confederation, more closely resembling Republicans in the United States than their counterparts in other regions of Canada. In Canadian issues particularly, Albertans have generally less conciliatory attitudes toward the Indigenous, particularly low views of Ontarians and the Québecois, and reject the principle of national bilingualism more than any other province. Albertans are less likely to endorse multiculturalism than Easterners and are more critical of high immigration targets.1

The Freedom Convoy, which was organized primarily by Albertans, drove to Ottawa and blocked many border crossings in 2021 to protest Covid-19 vaccine mandates and lockdowns. Data shows few Canadians supported the movement, whereas it was lauded by American Republican media. Most interestingly, at convoy organizer Dwayne Lich’s bail hearing, he appealed to his freedom of speech as per his first amendment rights. The judge was confused, and rightfully so. The first amendment to the 1867 BNA Act is that which allowed for the entrance of Manitoba into Confederation.

The ethos of Alberta more closely aligns with “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” than “peace, order, and good government.”

While Americanism is present in the political beliefs of Albertan Conservatives, it is even more aesthetically conspicuous.

The rodeo, the cattle ranch, the cowboy, the roughneck, are American images which shine forth in the Albertan prairies. Country music and two-stepping are deeply ingrained within small towns here, as are beer and fireworks. The archetype of the “good old boy” is emulated naturally. Each town has a yearly “stampede” and a country music festival.

American-style Evangelical Christianity found a home in Alberta like no other province. For a span of 33 years, from 1935 to 1968, Alberta was governed by radio evangelists—“Bible Bill” Aberhart and then Ernest Manning—both of whom ran a radio show on Sunday afternoons called “Back to the Bible Hour” on top of their duties as premiers. Though Alberta is largely secular now, this tradition of Evangelicalism remains to the present.

This is not to mention the major pipelines which connect Alberta to the United States. These pipelines do not only transport oil; pipelines are metaphysical—they transport culture. They are sustained not by steel, but by will. They link hinterland to heartland and develop a feedback loop between them. Pipelines, as such, work both ways. They bring oil to America, but also bring America to Alberta. They are mechanisms of cultural transmission, as are roads and railways. The pipeline draws Alberta firmly within the American sphere of influence.

And then, there are certain strange… I will call them blips, certain images which are noticeably out of place—where Americanism is not only imitated, but instantiated. A Confederate flag flying from a pickup truck. A Trump 2024 sign on someone’s lawn. “Let’s Go Brandon,” an anti-Biden slogan, spray painted on the side of a building. These moments are like glitches in the Matrix, wherein an eerie cognitive dissonance creeps in. Americanism feels like a dark force pervading the land, and on rare occasions, baring its teeth.

It is essential to notice here that the aesthetic dimensions of Albertan Americanism were present before the political dimensions.

Largely until the Leduc No.1 strike in 1947, Alberta was one of the poorest provinces in Canada. Despite its large American population, Alberta was a hotbed for Socialism, Farmers’ Unions, Social Credit doctrine, and the New Democratic Party. Rather than being the bastion of freedom, individualism, and small government that it is today, Alberta was a distinctly communalistic province. The transition from then to now was gradual, even with the overnight wealth generated from the oil booms in the 1950s and 1980s. Through this transition, what persisted was rodeos, cowboys, and country music, being further ingrained in the Albertan imagination.

It is intuitive to suppose that aesthetics is downstream from politics. I posit the obverse—that politics is downstream of aesthetics.

I use “aesthetics” deliberately here. For, it is not only that these phenomena are taken in by the senses, but that they are also judged. To make an aesthetic judgement is to deem something pleasing or displeasing to the senses. One makes this judgement according to their taste. One’s taste is influenced by many factors, including beliefs, experience, or innate aesthetic sense. One does not need to understand or express their taste in rational terms for it to constitute the criterion of aesthetic judgement. Taste, as I define it, simply is this criterion.

When making aesthetic judgements, it is intended that one’s taste reflects what is true, and that what one deems pleasing to their senses is also pleasing to others—namely, that it is beautiful. It is thus that the subjective experience of sensing leads one to make objective judgements about the world. Plato was right to deem the True and the Beautiful both manifestations of the Form of the Good. For, when someone deems something beautiful, according to true criteria, they also indicate that it is good. As such, by judging something aesthetically, one also tends to judge it morally. If something is beautiful, then it is natural to believe that it is also right. In folk tales from diverse civilizations, ugliness is tantamount to evil—suggesting that it is a universal and transhistorical tendency to conflate beauty and goodness.

Whereas an aesthetic judgement discriminates between pleasure and pain, political judgements discriminate between good and bad, again on the basis of true criteria. Political judgements are in this way rational, whereas aesthetic judgements are sensual. These are not separable processes, as both are interwoven through the interaction between the Beautiful, the True, and the Good. There is, therefore, an political component to aesthetic judgements, just as there is an aesthetic component to political judgements.

The sensual, however, far overpowers the rational. Sensual stimuli are far more scintillating than rational stimuli. Too often we pursue what is pleasurable above what we understand to be good for us. The spiritedness of political debate suggests that there is something more than merely the rational faculty at play. This spiritedness seems more proper to the sensual faculty. In politics, aesthetics overrule reason. The world people wish to bring about through political intervention is not one that is more reasonable, but more amenable to their senses.

Political judgements are often based upon aesthetic criteria—one’s taste—which is shaped by experience, a parochial way of life. That one’s experience shapes one’s political beliefs is an uncontroversial claim. Different regions, having different concerns and priorities, tend to foster different beliefs. However, what is neglected is the aesthetic component of this process. Whereas in a purely provincial society, political belief was intimately tied to self interest, now, in a world with great regional mobility, there is a chasm between self interest and political belief, similarly suggesting a distinction between the aesthetic and rational components of that belief.

Plato had an early understanding that political belief is often a matter of aesthetics in his image of the cave. Those at the bottom of the cave are habituated not by direct teaching, but by the shadows on the wall of the cave, created by a sordid puppet show, with public artists manipulating the light of truth into a shallow semblance of the real thing. Political ideology, as indoctrination, is thus engendered by aesthetic experience, with the visual sense being the most potent. One is freed by realizing not the falsity of belief, but the falsity of an image which seeks to describe the Whole.

If we revisit the Albertan experience, we see how aesthetics informs politics in a fundamental way which is neither rationally coherent nor purely self-interested. In imitation of the Americans, patriotism becomes jingoism and flag-waving, as opposed to the sober and cautious patriotism on which Canada was founded. The symbols and images present are particularly indicative of the aesthetic dimension in their thought. Brazen and offensive political messaging feature on stickers, whether “Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark,” “I Love Canadian Oil and Gas,” or “F*ck Trudeau.” Flags are highly indicative of American import, with the Confederate and American flags being common in the rural West. Americanism spreads visually, after which it is adopted politically.

One of the most persistent arguments made in the West on why annexation is desirable is that the United States has the second amendment, protecting legal gun ownership. This argument is borne of perceptions that gun ownership is severely restricted here and that the Canadian government is liable to confiscate legal guns. This perception does not accord with reality. Canada has the sixth highest rates of legal gun ownership in the world. Relative to most other places in the world, guns are widely accessible. In 2020, the Liberal Party of Justin Trudeau announced a ban on “assault style weapons” and a buyback program for such illegal firearms, with a target of collecting hundreds of thousands of guns. However, participation in the program is voluntary; People are generally unwilling to give in their guns and law enforcement is unwilling to enforce the program. The number of firearms actually collected through the program currently sits at around twenty. The perception that guns are under threat in Canada simply does not accord with the reality of the matter. The Second Amendment proves to be more of a symbol, part of an aesthetically American package, than a concrete measure which would protect gun ownership in Canada.

The primacy of the aesthetic is observable in the sphere of Alberta’s religious landscape. Alberta is about as secular as any other province, and yet Albertan Conservatism proves to be the most socially conservative mainstream Canadian ideology. This is explicable in light of the Albertan Evangelical heritage, with values passed down not as beliefs rationally derived from religion, but embedded into a way of life through religion, and so present visually even after the religion has lost its prevalence. Albertan Conservative values on abortion, same-sex marriage, individualism, and hard work, are all products of their Evangelical heritage, without the Evangelicalism being present. Yet, they continue to cohere aesthetically. It is difficult to drive through the Albertan countryside without seeing billboards which advocate against abortion and drug abuse.

The prevalence of country music is also a highly prevalent and distinctly American phenomenon. Country music is a strangely descriptive and self-referential genre. It acts as an effective vehicle of cultural transmission, describing a lifestyle—characterized by hard work, cold beer, trucks, farming and ranching—then to be instantiated. Country music conjures an image, which informs ones taste, then shaping one’s criteria for aesthetic judgement, from which political belief is derived.

It is noteworthy that, whereas some of these images were ever present in the Albertan lifestyle, some of them are imported. When my argument thus far is put into simpler terms—that experience, having an aesthetic dimension, shapes political ideology—it is uncontroversial. When the experience has been done away with, however, and yet the ideology still remains, the aesthetic dimension comes into the fore. There is no experience which should imbue the Albertan ethos with Americanism, and yet it is present. The focus, then, turns on to how these images are conveyed. Images can be transmitted which inspire political beliefs, despite the absence of the experiences antecedent to those beliefs. In the modern age, this is done via mass media.

Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose corpus is dedicated to understanding the ways media shape man and society. His key insight is often summarized as “The medium is the message,” meaning that the medium used to convey a message is as important as the content of that message. Different media create different psycho-social states in their users and audience, and thus colour the content they present.

In The Gutenburg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, McLuhan describes the profound shift European society underwent with the development of the printing press, transitioning from an audible to a visual culture. Whereas, before the printing press, most intellectual activity occurred through the voice, reading aloud or conversing, the printing press made the written word so widely accessible that it became the dominant way of obtaining information. This was not a simple exchange of one medium for another; the printing press changed the minds of men in a fundamental way. This brought about what McLuhan called a “tyranny of the visual,” wherein sight became the dominant sense, and images became more enticing than sounds. Whereas audible culture is fluid, unique, and romantic, visual culture is fixed, standardized, and austere. The mass-production possible with the printing press conduced the mind to seek standardization elsewhere, in nationalism, rationalism, and standardized weights and measures.

For McLuhan, the tyranny of the visual persisted into the twentieth century, at which point mass media began to dominate. Most forms of mass media did not replace, but heightened, the dominance of the visual. Photography allowed for the mass production and distribution of images, meaning that someone’s visual understanding of the world was no longer dominated by their immediate field of experience. Television was far more sensually stimulating than the written word could ever be, enthralling audiences. New visual art forms, such as Abstract Expressionism, were fast, bright, and vivid. As these media spewed a volley of intense and evocative imagery, the mind sped up and the attention span shortened. People became accustomed to immediacy—of everything everywhere all at once. When a man can view the war in Vietnam from his living room, borders collapse, temporality ceases, and a man becomes a part of the world, not only of his world. These media foster connection, all the more real because it is a visual connection. This immediate connection is what McLuhan referred to as the “global village” in which we all live.

Many developments in media have occurred since McLuhan. Most notably are social media. The instantaneity of mass media is further intensified on social media such as Facebook, Instagram, or Substack. When one can immediately send a message to and share images with someone on the other side of the world, difference, distance, and mediation cease to exist. Social media conduce to impatience in this way. That our affection is so spread out and cheapened, while the superficiality of encounters increases, man is made lonely, and instead seeks attention. So does social media create a unique psychosocial state, ever heightening the tyranny of the visual through bright and evanescent screens.

Along with social media came the tools for us not only to share images, but create and curate them. We can alter photographs to enhance them however we please. We can create images and visual art with more ease than ever. We can cultivate a feed which shows us exactly what we want to see. AI takes these things to an even greater extent. Generative AI, whether text or art, synthesizes results from the internet and produces whatever content it is prompted to create. Ask and you shall receive. What is real and what is not is blurred through this process. If one asks AI for a picture of a dog, what one finds is not an actual dog, but an ideal image of a dog, synthesized from thousands of actual dogs. One can call it all artificial, but that would imply that it is fake. On the contrary, there is an element of the real within it. It is simply too real. Social media and generative AI warp and prey upon our perceptions. We demand a perfected version of the real and it is provided. Our expectations are thus altered. The real no longer suffices. We demand the perfected version of the real. We demand the hyper-real.

This is what Jean Beaudrillard called the simulacrum—the copy without the original. It is more real than the real, though it does not correspond to the real.

The age of the hyper-real is characterized by the perfection of the real. This perfection constitutes an aesthetic ideal. This ideal, in turn, becomes our expectation. We are inevitably disappointed when we encounter the real, which turns us back into the realm of the hyper-real in a vicious cycle. The hyper-real, as it is primarily, though not entirely, an aesthetic phenomenon, is clearly visible everywhere on the internet, from girls artificially inflating their lips for photos to people on Substack using AI images as profile pictures and personas. For my purposes, it is necessary to highlight the phenomenon of aesthetics, as they are called on social media.

What is called an “aesthetic” is, in my terms, an aesthetic ideal (by its very title we see another irony of the age of hyper-reality: equating the real with the hyper-real). It is a carefully curated collection of images—clothes, props, settings—which constitute a lifestyle that only exists in one’s mind. People then attempt to instantiate this lifestyle, however imperfectly. Their own life—the real—is judged against this aesthetic ideal. That one can create a lifestyle and cultivate a taste completely devoid of experience shows how easy it is to enter the realm of hyper-reality. That one’s aesthetic becomes central to their identity demonstrates the tyranny of the visual and our nature as aesthetic creatures.

One’s aesthetic, meaning their aesthetic ideal, is politically coded. Conservative finance bros wear suits, while radical feminists shave their heads and get tattoos. This is hardly an accident, given the relation between the aesthetic and political. However, given the spread of aesthetic ideals via social media, this means that political beliefs can infiltrate a community in which they would ordinarily not arise, given that they conflict with the lifestyle engendered by that place. Before this, political belief was a matter of mimesis in the colloquial sense, a reproduction of what we see around us. Now, political belief is mimesis in the classical sense, of a perfected image of the world according to its own laws. This has opened a rift between taste and experience, revealing that politics are downstream from aesthetics. We see this often in the modern world—anomalies, black sheep. I have seen woke justice warriors in the Patch and wannabe conservative rednecks in the city. I speculate that it is through social media, through their participation in hyper-reality, that they come to possess such beliefs.

Beliefs are more compelling when they are part of a package. As such, political ideologies, which are sets of coherent beliefs, are not rationally, but aesthetically coherent. When a political ideology corresponds with an aesthetic ideal, that ideal acts as a Trojan horse to usher in the belief. MAGA is an aesthetic, as is Wokeism. Communism, feminism, and nationalism are all aesthetic movements as much as they are political. We can speculate that the failure of small-l liberalism in our century is the lack of accompanying aesthetic ideal. After all, what is the aesthetic of liberalism? Business casual attire? Minimalism? The International Style of architecture? Similarly, I speculate that libertarianism fails to capture hearts and minds precisely because it is a rare example of a rationally self-consistent ideology, not an aesthetic movement.

It is, therefore, as an aesthetic package that Albertan Conservatism is revealed to be self-consistent.

This package comes with many different aesthetic ideals. There is the ideal of the roughneck—the man of the Patch—who works the rigs, drives a suped-up truck, is strong and muscular, has a wealth of expertise and knowledge at his task, and proudly wears a “F*ck Trudeau” sticker on his hard hat. This is the type, and men strive to be the tokens. Downstream from this aesthetic ideal are certain political beliefs—anti-environmentalism, distain of bureaucracy, desire for small government, and a love of individual freedom. He is master of his task; any restriction on his agency is an insult to his person.

Another aesthetic ideal is the cowboy—a distinctly American image—which is common among the farmers and cattle ranchers of rural Alberta. The cowboy wears a Stetson and boots, ranches and rides, two-steps to country music, and is intimately tied to the land. Being tied to the land so lends itself to patriotism and nationalism (though since this is an aesthetic ideal which descends from America, the patriotism is distinctly American). With the cowboy, as with the roughneck, the personal agency derived from his task, in this case stewarding the land that he owns and having ultimate liberty on his property, leads him to love freedom. Since he is grounded upon the earth, he is distrustful of the sky—anything which descends from government, big business, or forces which he does not understand, is met with incredulity. This foments into an anti-establishment attitude.

As I have discussed, Evangelical Christianity also serves as an aesthetic ideal, which persists despite irreligiosity on the prairies.

We see that the aesthetic ideal is often presented in the form of a character, or an archetype. This is the most powerful kind of aesthetic ideal because a man may emulate it with the most ease. When a man adopts the appearance of this archetype, he naturally fills in the gaps. An aesthetic ideal can also descend as a way of life, in which case man must alter his behaviour to instantiate the ideal. Or, an aesthetic ideal can appear as a style or artistic movement. Though more abstract, a man can adopt and embody the essence of such a movement. It is not difficult to see how there is a particular man engendered by the American Realist paintings of Hopper or the Abstract Expressionism of Pollock. Both movements are upstream of certain political beliefs—the former, embodying the dignity of labour and the hardships of blue collar life, while the latter constitutes a rejection of the conservative establishment and the questioning of norms.

My time in the oil sands only convinces me further that politics and aesthetics are inseparably linked.

Alberta being a destination of American cultural import is in part an economic issue. That Alberta’s economy is reliant on oil markets in the United States brings Alberta into the American sphere of influence. Pipelines, which connect a resource hinterland to a manufacturing heartland, are the vehicles of cultural import. When one region is economically reliant on another in the way that Alberta is, a paternalistic relationship is established. Alberta looks up to the United States. There is proof of this in that political Americanism only arose in Alberta around the oil boom of the 1950s, when Albertan oil needed markets for sale and refinement which Eastern Canada could not provide. Saskatchewan, similarly, was highly collectivistic until their most recent oil boom. This is in contrast to Manitoba, who, without such an economic tie of dependency to the United States, is still firmly within Ontario’s sphere of influence, and so American images do not pervade there.

On my drive to work, from the city of Cold Lake to the Imperial Oil project northwest of town, I see “Fuck Trudeau” flags and bumper stickers on trucks, and myriad Canadian flags, with at least as many Albertan flags. Cattle ranches, wheat fields, and oil leases dot the prairie landscape. My coworker in the truck is talking about “faggy Ontarians” and how Trump should annex Canada. On our day off, a crewmate takes us to an abandoned oil lease near town to shoot clay pigeons. Driving there and back, the only acceptable radio station is country music. The men on my crew have steady girlfriends, get married young, and have family values, even if none of them are Christians themselves. The towns in the Oil Patch are proud of their ties to the oil and gas industry. In Cold Lake, banners with pictures of pumpjacks line the main stretch running through town. In the local Mark’s Work Wearhouse I find a selection of “I love Canadian oil and gas” t-shirts and hats. In a Tim Horton’s, I hear a conversation between a group of old-timers launching into jeremiads about the state of our country and Justin Trudeau.

It all starts to make sense. I understand the political temperament of these men—their ideology is embedded in the images, symbols, and way of life encountered in the Patch. Even as much as they have forceful political beliefs, their aesthetic sense is far more powerful. This is why there is no cognitive dissonance when a man flies a Confederate flag on his property. It may be irrational, but it is in complete conformity with the aesthetic package presented to him.

There is a beauty in this aesthetic ideal. There is an allure to the realm of hyper-reality. The cognitive dissonance fades away. It all starts to feel right.

All this is empirically demonstrable, as shown in data from Mathieu, Félix and Evelyn Brie, Un Pays Divisé: Identité, Fédéralisme et Régionalisme au Canada (2021), Les Presses de l’Université de Laval.

>I speculate that libertarianism fails to capture hearts and minds precisely because it is a rare example of a rationally self-consistent ideology, not an aesthetic movement.

Far from being "rationally self-consistent" libertarianism is as swiss-cheesed as any other ideology. It's aesthetics may bear attraction, to a younger mind perhaps, but its logic?

Unsurprisingly, I wrote about this topic about 10 years ago. I think my reflections remain relevant:

https://contravex.com/2016/09/26/the-thing-libertarians-get-wrong-about-property-rights-or-why-im-not-a-libertarian/

https://contravex.com/2016/10/02/on-the-ultimate-justification-of-the-ethics-of-private-property-by-hans-hermann-hoppe-adnotated-part-3/

Good article. I've been thinking about aesthetics as it relates to Canadian nationalism lately myself.